Posts from — November 2011

Lumiere — A Festival of Light

Last weekend I was lucky enough to get up to Durham, in the NE of England, to spend a couple of nights experiencing the latest event from Artichoke, titled Lumiere. And a magnificent event it was too.

Lumiere was in fact how I first heard about Artichoke, via a TV documentary on Sky Arts (in the old days when I used to subscribe to Murdoch TV — we’re now on Freesat). That first Lumiere happened in 2009, and of course I’d missed it. But they planned to do it again, and when I heard about the 2011 event I was quick to block out the time and book a hotel.

The event, which brought dozens of international artists working with light into the heart of the mediaeval city, turning it into a vast illuminated art gallery, lasted over four nights, nominally from 6–11pm, and featured around three dozen separate exhibits. Some of the higher profile installations were in the city centre, but many were rather further out, and in fact you would have needed all four nights to catch everything. I only had two nights, and that simply wasn’t enough — I probably saw about 2/3 of the installations and missed some that I really wanted to see. Thankfully the weather was kind to us — no rain and in fact quite warm — a good deal warmer, in fact, than the last Artichoke event I attended, Dining with Alice, back in May!

What I had rather underestimated was the number of people who would throng the centre of the ancient city as night fell and we approached 6pm. We gathered next to the statue of the Marquess of Londonderry — not one of the nicest people in life, allegedly — who had been transformed, thanks to Jacques Rival, into an immense snow-globe with the words “I Love Durham” on the plinth. Hehe.

The crowd control was excellent, despite the enormous numbers of people, but what the organisers could have done that would have helped was to have had a fairly serious PA set up in the Market Place so that the crowds could be informed about what was happening. The bull horns in use had an effective range of about 10 feet, so most of the time none of us had any idea what was happening or going to happen. It turned out that we were waiting to be allowed up the cobble streets to the Cathedral, but we didn’t all know that. However, that is the only mildly negative comment I have about the whole festival, and hopefully the planned 2013 event will take this suggestion into account.

Via Twitter, @ArtichokeTrust asked what my favourite exhibit was, and it’s really difficult to say. Of course the amazing son et lumiere at the Cathedral, highlight of the original 2009 show, must rate up there, and that’s the first thing we were effectively queuing to see. Titled Crown of Light, it consisted of marvellous images of the Lindisfarne Gospels and much more, illuminating the front of the Cathedral with multiple sections sliding up and down independently, accompanied by a powerful surround audio and music soundtrack including actual environmental recordings from Lindisfarne itself (though I think it would have sounded better in Ambisonics, of course). Crown of Light was created by Ross Ashton, Robert Ziegler, and John Del’ Nero.

It’s actually quite hard to convey much of a sense of Crown of Light as it was so immense. But here’s a taste:

The above video includes two extracts, one from near the beginning and the other from the end. It’s a hand-held mini-camera running at its highest sensitivity, so it’s not wonderful quality, but hopefully you’ll get the idea. The first extract is 16:9 and the second pillarboxed 4:3, the latter showing rather more of the building.

Following the presentation (there were three per hour), we could either go off to the left, and down towards the river, or we could file into the Cathedral itself, where there were some amazing things going on in the Nave, the cloisters and the College gardens behind.

Compagnie Carabosse had hung the Nave with lamps made of white vests on frames, while at the far end of the Nave, next to the pulpit, was a gentleman performing on electric guitar, synth and vocals, in a rather cool neo-Steampunk environment. This photo of him is a bit ropey, but hopefully you get the idea from that and the (even more ropey) raw iPhone video below (the audio improves dramatically at 2:22).

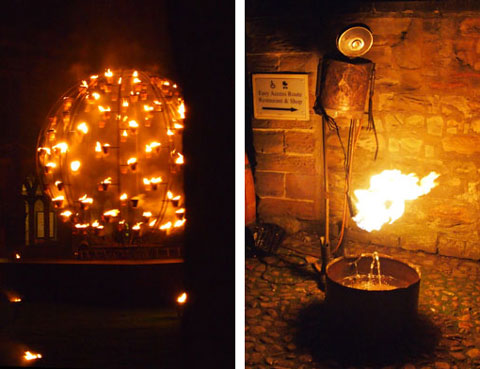

In the cloisters and gardens it was fire — with amazing metal frameworks and sculptures with flames issuing from various parts — from the enormous (a rotating globe covered in firepots in the cloisters) to fiery fountains and strange little figures.

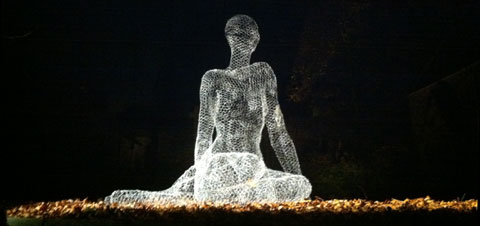

Emerging from the gardens through an ancient archway, we turned down the hill to be confronted by a sequence of marvellous illuminated wire-mesh sculptured human figures, sometimes flying, sometimes sitting nonchalantly on a roof, or reclining in a garden. These were Les Voyageurs (The Travellers), by Cedric Le Borgne — a number of French artists were represented here.

We proceeded down the hill, marvelling at these overhead, nearby and distant figures, until we came to Prebends Bridge, which gave us a passage through a progressive rainbow of colours.

And then it was back towards the centre of the city along the riverfront, with the trees and bridges illuminated by gently shifting coloured lights — and virtually all the lights in the Festival, incidentally, were low-energy varieties, with some City lighting turned off so the overall energy impact of the event was minimal.

Some of the exhibits were lower-key, but nonetheless effective. Real and imaginary stories were told in illuminated text; a clock on a far building spelled out the time in lower-case Helvetica; and a series of illuminated panels hung high above the narrow streets. Possibly the best-known artist’s work at Lumiere was Tracey Emin’s: an illuminated phrase, “Be Faithful to your dreams” in blue, handwriting-style text on the side of the chapel in a disused graveyard, approached along a path lined with trees softly shining with slowly shifting colours.

Elsewhere, an enormous light bulb made of lights hung over the river Wear:

…while commonly-thrown-away objects were montaged and lit with LEDs:

We had an invitation to join friends and sponsors in the Town Hall on the Saturday night, which was good fun, and I had some interesting chats — with Artichoke co-Director Nicky Webb and with the people who organised the food for Dining With Alice, who had quite a tale to tell, to name but two.

All in all, Lumiere 2011 was an amazing, magical, marvellous festival of lights and art – exactly what I have learned to expect from Artichoke. I do hope they are able to do it again in 2013.

For more videos of Lumiere (including some from the first event in 2009) on Vimeo, click here.

November 23, 2011 Comments Off on Lumiere — A Festival of Light

Christmas(ish) At Beamish

Whenever I’m in the NE of England, I try to get over to Beamish - “The Living Museum of the North”. It’s a wonderful place built around a road/tramway loop on which run vintage buses and trams.

On this occasion (20 November) I was up for the weekend to go to Lumiere in Durham, so nipping over was a chance I couldn’t miss. It was foggy on leaving Durham but approaching Beamish the sun came out and it was gorgeously sunny until the drive home, when the fog closed in again.

Different sites around the tramway loop recreate different eras, each created from buildings that have been lovingly transplanted from their original sites: the Town, for example, is Edwardian, with a Bank, a gorgeous Masonic Hall (rebuilt with the help of the Masons, apparently), a Co-Op department store, sweet shop/factory and lots more. It also has an adjacent Steam Railway and station and a steam-powered fairground.

The Pit Village is perhaps somewhat earlier, and features a colliery and a relatively new addition: a coal-fired fish & chip shop that uses beef dripping to cook with, resulting in utterly tasty meals that you have to queue for twenty minutes or so to get, it’s so popular. Yet another area, Pockerley, is more Georgian, with a Waggonway that features steam locos from the earliest times and Pockerley Old Hall. I’ve talked about Beamish before, here.

From this time of year until Christmas itself, Beamish is having a series of Christmas weekends, including Santa’s Grotto somewhere over by Pockerley I think, complete with snow, an ice-rink in the Colliery Village (above), and decorations up in the Town.

I had to pop into some of the terraced houses, several of which contain businesses, such as a solicitor’s and a dentist — the torture chamber itself is shown below. In those days you would have had the option of (unregulated) nitrous oxide (with a fair risk of death) or cocaine as anaesthetics, the latter effectively removing your short-term memory, so things hurt but you didn’t remember it (rather like intravenous Valium it would appear, which I always loved as an adjunct to dental operations).

Another house included period Christmas decorations in the front room.

Across the street is a little park, with a bandstand, and there was the Murton Colliery Band preparing to play some suitably seasonal music, which they proceeded to do beautifully.

Here’s some video of extracts from their programme:

The band was formed as the Murton Gospel Temperance Blue Ribbon Army Band in 1884, and players were requested to wear a blue ribbon on the second button of their waistcoats. They became Murton Colliery band in 1895. When the colliery closed, the band became self-supporting — and it still is today. They’re also one of the few remaining bands to continue to call itself a ‘Colliery Band’, and they still proudly march through the village during the Durham Miners Gala and Armistice Day. I don’t know about you, but brass band music and Christmas do seem to go together rather well.

There was time for a good wander around and trips on some of the trams — including a 1930s enclosed double-decker Blackpool tram, which is technically a little late for their re-creations but very impressive — and I had some good chats with the tramway staff, noticing that they wore the archetypal “wheel and magnet” emblem of British Electric Traction (later to become the parent, surprisingly, of Rediffusion Television) on their caps. The shop at Beamish should sell those cap badges — I would have bought at least one.

There was time for a good wander around and trips on some of the trams — including a 1930s enclosed double-decker Blackpool tram, which is technically a little late for their re-creations but very impressive — and I had some good chats with the tramway staff, noticing that they wore the archetypal “wheel and magnet” emblem of British Electric Traction (later to become the parent, surprisingly, of Rediffusion Television) on their caps. The shop at Beamish should sell those cap badges — I would have bought at least one.

Finally it was time to head off on the 3+ hour home, and soon after getting back on the A1 the fog closed in, and it ended up taking a good deal longer than that. But it was a great day out.

November 23, 2011 Comments Off on Christmas(ish) At Beamish

75 Years of BBC Television

Wednesday 2nd November saw the 75th anniversary of the opening of the BBC Television Service.

To commemorate the event, the BBC held a special celebration at Alexandra Palace, where the Service opened.

Originally, the intention was to hold a special Open Day on the 2nd, at which members of the public would be able to visit the studios and see audio-visual presentations. However this was eventually moved to November 5–6, leaving only an internal BBC event happening on the actual day.

I managed to obtain an invitation, for which my thanks to the ebullient Robert Seatter, head of BBC History, and technology journalist Bill Thompson.

The invitation said “3:45 for 4pm” and as a result I found myself in the Alexandra Palace Tower end car park well in time for the off, giving some time to take in the views over the city, experience the continual wind and enjoy some dramatic skies over this “Palace of the People” located at the highest point in North London.

When the BBC decided on Ally Pally as the site for the new BBC Television Service in the wake of the Selsdon Report in 1936, the place was already decaying somewhat. It’s a process that has continued since BBC Television left here several decades ago, and although the team now fronting the Trust that runs the site today is incredibly, and impressively, enthusiastic and upbeat, there is no way it can be other than an uphill struggle in these austere times. But you can’t say they aren’t trying hard and I wish them every success.

The BBC still maintains active offices in the block under the mast. But instead of entering through the doors there, adjacent to the GLC blue commemorative plaque on the wall, we were motioned into an entrance along to the left, up a metal ramp and into what had originally been the Transmitter Hall. It may be noted that this was probably not the first, but possibly the last, time that anyone had the bright idea of placing a pair of powerful VHF transmitters and a pigging great set of transmitting antennae right next to a set of television studios full of sensitive equipment.

Inside, the room had been decorated with panels against the walls, each carrying information and images of some aspect of Ally Pally TV history, and a free-standing photo display of historical images, mainly provided by the Alexandra Palace Television Society. A jazz quartet played suitable 1930s style music; servers glided among the assembled invitees dispensing water, orange juice or Prosecco.

Inside, the room had been decorated with panels against the walls, each carrying information and images of some aspect of Ally Pally TV history, and a free-standing photo display of historical images, mainly provided by the Alexandra Palace Television Society. A jazz quartet played suitable 1930s style music; servers glided among the assembled invitees dispensing water, orange juice or Prosecco.

We had the chance to mingle and chat, and I was very pleased to meet TV cook Zena Skinner, who probably coined the phrase “Here’s one I made earlier” — though in her case she really had made it earlier, herself; I also met Professor Jean Seaton, the BBC’s Official Historian and Professor of Media History at the University of Westminster; and talked briefly to John Trenouth, Technology Adviser to the BBC Collection, whom I met during his time at what is now the National Media Museum in Bradford.

In the centre of the room, a make-up table and lights were set up, where various young women were being made up using the colours required by the Baird System.

When the BBC Television Service was established, the Government required two television systems to be used. On the one hand was the all-electronic Marconi-EMI system, which offered 405 lines, and on the other was the Baird electromechanical system which delivered 240-line television. Early on, it became evident that the Marconi-EMI system was significantly superior, but it had been Baird who had tirelessly promoted television as a concept, and lobbied the GPO over licensing and the Government to legislate for a Television Service. Baird highlighted the fact that his was a British invention – though it could equally legitimately be claimed that the Marconi-EMI system was British. Almost certainly the Government decision, a typical British compromise, was made at least in part to avoid suggestions that they were turning down a British innovation, the decision mandating the use of both systems on an alternating basis for six months before a choice was to be made before the two. The problems experienced with the technological dead-end of the Baird mechanical scanning system resulted in the decision — in favour of Marconi-EMI — to be made after just three months.

Baird Television actually used two systems. The fundamental feature of both was a “flying spot scanner” in which, almost completely counter-intuitively, the scene was scanned with a spot of light and photocells collected the light reflected from the subject. The “Spotlight Studio” used nothing more than this; the Intermediate Film Technique used a conventional film camera, exposed film from which was then passed immediately through developer and highly poisonous cyanide-based fixer (particularly nasty when it got loose), then scanned with a a flying spot actually under water. The flying spot scanner was very sensitive to red light, so if you were appearing in the Spotlight Studio, you needed the special make up: black lipstick, blue eye-shadow and a pale white face. Very neo-Goth. You checked it by looking through a red gel.

This was the make-up that was being applied to the young ladies at Ally Pally on the 2nd. Apparently the idea had originally been that BBC London would be sending a crew up to cover the party, but they had pulled out and the job was left to an enthusiastic team from BBC News School Report.

Meanwhile, we were treated to welcoming presentations: by the PR gentleman from the AP team, and from Robert Seatter, who encouraged us to relinquish our glasses and proceed upstairs to Studio A.

There were two main studios at Ally Pally originally, one above the other. Studio A was the Marconi-EMI studio, while directly above it was the Baird studio, Studio B. You can’t go into B today, because it’s riddled with asbestos and things are likely to fall on your head. But Studio A is accessible. At one end of the room is a tableau representing the production of the magazine programme Picture Page, which ran from 1936–39 and 1946–52 and was initially presented by Joan Miller.

Around the room are assembled old TV sets, and various exhibits in the room itself included an EMItron camera, which John Trenouth of the National Media Museum in Bradford kindly removed the lid of so we could have a look at the innards (sans tube).

In Studio A we were treated to a couple of brief audio-visual presentations, the first assembled mainly from clips from the film documentary Television Comes To London, which was made to tell the BBC Television Service story in 1936. Rebecca Kane, the MD of Alexandra Palace Trading Ltd, introduced Michael Aspel, a newsreader at AP during the period when BBC Television News was based here, to cut the cake.

And what a cake it was: made in the form of an old bakelite television with a picture of Alexandra Palace on the screen, deliciously thick icing and succulent innards. Very nice.

After that, we all wandered around Studio A and chatted to each other. I got into an amusing discussion about the way in which the Television Service closed down at the start of the Second World War, on September 1st, 1939 – about which a number of myths have arisen, most of which are incorrect (including the perpetuation of the main myth in Alan Yentob’s Imagine documentary, re-shown on Wednesday) – see The Edit that Rewrote History on the Transdiffusion Baird site, which includes a number of articles on television prior to 1955.

And then we gradually sloped off home.

See also:

The birth of television: the “Baird” microsite at Transdiffusion

75 years on from BBC television’s technology battle — a nice piece by John Trenouth

BBC Celebrates 75 Years of TV — Nick Higham visits Alexandra Palace

November 5, 2011 Comments Off on 75 Years of BBC Television