Gryphon’s ReInvention Reviewed

Gryphon — ReInvention

Reviewed by Richard Elen

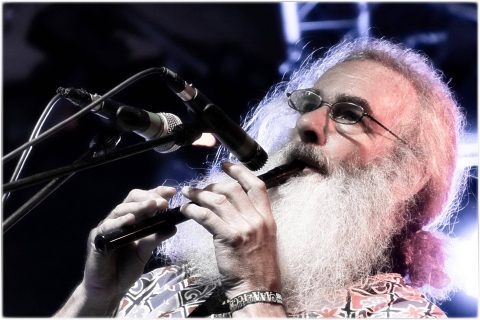

The story of the band Gryphon goes back to the beginnings of the 1970s and the London College of Music, when multi-instrumentalists Richard Harvey and Brian Gulland — who were playing Renaissance woodwinds in Early Music band Musica Reservata — got a small group together under the name Spelthorne. Soon the original lutenist left, and Graeme Taylor (guitars and vocals), who had been at school with Harvey, joined the group, swiftly followed by David Oberlé on drums, percussion and vocals. Almost at once the band changed their name to Gryphon after the beast in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland. The band started by playing authentic mediaeval and Renaissance music but soon branched out and started writing their own material. Lawrence Aston, A&R at noted folk label Transatlantic Records, heard the band and signed them. Their first, eponymous album was released in 1973.

The band went on to make three more albums for Transatlantic: Midnight Mushrumps, based around their music for Peter Hall’s National Theatre production of The Tempest; Red Queen to Gryphon Three, and Raindance, the latter which I had the pleasure to record and co-produce in the midsummer of 1975. Various disagreements between the band and the record company resulted in Gryphon moving to EMI’s Harvest label, where they released one album, Treason, in 1977. By this time the band was, as were many high-quality acts of the time, being eclipsed by punk artists who could go out and gig for far less money per night than a complex outfit like Gryphon.

Thus the band became dormant, and so it remained until 2009 when they got together for a reunion concert. By then there had been rumours of a new album in the works, but nothing emerged. Richard Harvey left the band in 2016 to pursue his extensive solo interests, and well-known music library composer and multi-instrumentalist Graham Preskett joined. After a series of concerts a new album, the first for 41 years, was announced: ReInvention, released in September 2018.

The lineup on the album includes original members Gulland, Oberlé and Taylor, with the addition of the aforementioned Preskett, Rory McFarlane on bass and Andy Findon on a range of woodwinds. All the pieces on the album were written by band members: there are no arrangements of traditional pieces here as characterised the first two albums.

ReInvention kicks off with Pipeup Downsland DerryDellDanko — a Gulland title if I ever heard one, which features interweaving recorders with staccato guitar phrases and chords, ultimately joined by pipe organ and saxophone. The piece wanders about lyrically and extremely pleasantly, and you never quite know where it’s going to go next. Out of this North Kent childhood idyll (for such it is), emerge Brian’s slightly avant-garde lyrics. “Stranger things than this have we passed / On our way to you today.” Indeed.

Next up is a piece from Preskett entitled Rhubarb Crumhorn. Yes, all the titles are fairly esoteric, but this piece itself is less so: it’s a very accessible number that builds gently from flute and organ to bassoon and into a fairly stately full band arrangement punctuated by warm Renaissance-sounding chords, and even a little theme reminiscent of something that Richard Harvey might have written. Then it’s off into a brisk gallop through a natty chord progression. Despite being written by relative “new boy” Preskett, this is a classic self-penned (as opposed to trad) Gryphon piece: had it been me sequencing this album, I would have opened the disc with it. There are, however, no crumhorns in this piece.

With A Futuristic Auntyquarian we are back in Brian Gulland territory, with an angular harpsichord-like opening — but only for a moment, as a nicely extended mock-Renaissance woodwind tune takes over, prancing lyrically over the underlying keyboards, to be joined by violin before the track goes off on a pleasant Gullandesque abstract wander with gentle exchanges between the instruments, ultimately joined by drums before going somewhat up-tempo and finally returning to a more robust take on the opening. Nice.

Recall that the band is named Gryphon after the character in Carroll’s Alice, and Graeme Taylor’s ten-minute setting of the poem Haddocks’ Eyes from Looking Glass becomes clear. Gently wandering solo bassoon opens, joined by clarinet and violin for a short trio until joined by acoustic guitar which brings structure to the wandering — and a tune, albeit quite an eccentric one. The piece picks up on the entry of Brian’s vocal, playing the part of the White Knight, in a dialogue with the voice of the Aged, Aged Man, played by Dave Oberlé, with a backing that gently rocks along, with occasional inter-verse returns to the lyrical wandering of the opening until we encounter a rougher solo section two-thirds of the way through, featuring wild heavily distorted and harmonised bassoon. The vocal dialogue gently slows to an apparent end — but it’s not an end at all, it’s a little instrumental romp that returns, finally, to the original gentle theme for the closing lines.

Hampton Caught is another Preskett number, with one of several punning titles to boot. He notes, “It starts somewhere near Sherwood Forest, lurches through harpsichord in three four, a slight hint of boogie in three, then a proper bit of electric guitar, before being interrupted unaccountably by a church organ, some strange rhythms and a build up. It culminates in the three four harpsichord section with additional string as it were.” Couldn’t have put it better myself.

Hospitality at A Price… (Dennis) Anyone For? is, of course, another Gulland number. The sleeve notes describe this as a “genial evocation of the 20s”, and it has some of that ultimately, but in fact it sounds rather like another Carroll poem with the exception of a couple of modern references. And suddenly: jazz crumhorns lead us off into a period piece and a very strange ending.

Dumbe Dum Chit (Preskett) takes its strange name from a mnemonic for a drum pattern to resolve this “bouncy bassoon tune in a strange rhythm”. A neat little number that follolops along, with in fact two strange rhythms rather than just the one, featuring not only bassoon but clarinet and guitar too.

Bathsheba is bass-player McFarlane’s sole composition on the album. Gryphon fans will know Taylor’s style and certainly Gulland’s, and Preskett fits beautifully into the Gryphon tradition, but McFarlane’s is a new voice and a very pleasant one at that. We begin with interweaving fractured phrases from bassoon and clarinet, joined by guitar and drums and, finally, a warm bass part that lasts only a few bars each time around before being joined by violin and woodwinds. One is reminded just a little of the North Sea Radio Orchestra or even the Muffin Men. The sleeve notes outline the controversial Biblical tale.

Sailor V, another by Graham Preskett, begins with a respectably nautical feel (you mean it’s not a pun?) featuring pipes and fiddle, joined by bassoon and guitar. It moves gently and lyrically along until gaining a brasher spring in its step, a touch of the Irish and some odd harmonica flourishes, as the piece moves through some lively changes in the course of its eight minutes to climax with an electric guitar section recapitulating the opening theme, doubled by other instruments in a very Gryphon culmination followed by a gentle wind-down. C’est la vie.

I have a particular fondness for Graeme Taylor’s song Ashes. One of my favourite Gryphon tracks, it was originally written for the 1975 Raindance album, which I engineered and co-produced, but was excluded from the release by the record company for some unknown reason. Its curious tale of afternoon cricket, King’s nephews and stallions, gently and lyrically sung by Brian, is a true joy. Summer that year at Sawmills studio near Fowey in Cornwall was hot, and I decided to record Brian’s vocal (twice), in the open, in stereo, with the mics a fair distance away from him so I caught the birds singing in the background. The version on ReInvention doesn’t have that, but Brian’s performance, albeit not double-tracked, is virtually identical to the original, as is much of the arrangement, though the solos are instrumented differently. Of course I prefer my version, but this one is very, very good 🙂 (You can hear the original on the Collection II album if you can find one.)

The album closes with The Euphrates Connection by Gulland, which begins with a low-pitched recorder theme, picked up by guitar and then a curious, short and unexpected vocal, developing into a complex interweaving multi-part instrumental, laced with Brian’s trademark angular and unexpected figures, a delicious rocky interchange between guitar, pipe organ and other instruments leading to a repeating sequence of short pipe organ chords, adorned only by reverb and the occasional sonority, before being joined by solo flute, bass, violin and guitar fragments and fading gradually to an end.

And so ends Gryphon’s first new album for over forty years. It’s beautifully recorded and produced by Graeme Taylor in his “Morden Shoals” studio: the overall sound is excellent and well-captured with a great deal of detail and care. The musicianship is of a uniformly high standard throughout and even the most complex angular and avant-garde passages are confident, sure-footed and executed with aplomb.

There are few artists who could return to the scene after four decades to such acclaim as Gryphon, as if their return has been awaited by us all for the entire time they were away. ReInvention provides exactly what it says, the band reinventing itself with new members and new directions. Unmistakeably Gryphon, it develops musical directions that were hinted at in earlier albums, takes them forward, and delivers an ultimately satisfyingly and eclectic result. One can only hope that it is the first in a series as Gryphon moves forward to new musical heights following its re-formation.

October 19, 2018 Comments Off on Gryphon’s ReInvention Reviewed

More Gryphon Restoration

As I noted previously, there are some technical challenges associated with recovering the recordings of the band Gryphon that I made in July 1974 during their landmark performance at the Old Vic.

A notable problem was the fact that there was a bass DI in the main PA mix (which was the basis for the recording, with the addition of a coincident pair of ambient mics) and this was often extremely loud in the balance — sometimes enough to cause intermodulation distortion with the rest of the mix (it’s possible that this was overloaded on the recording).

To give you an insight into the results of this factor, here’s another piece from the Old Vic tapes. This is Opening Number, the band’s, er, opening number. Note the effect of the bass entry about half-way through.

This is an example of why it may not be possible to get an album’s worth of tunes out of this recording. However it will be worth our trying to recover the stereo master tapes to see if the distortion is on there too (these transfers are from a copy).

August 21, 2018 Comments Off on More Gryphon Restoration

Restoring an Ancient Gryphon

This month has seen the release of the new album by old friends of mine, Gryphon. The album, ReInvention, is their first for 41 years: the band, re-formed and augmented, though now without the presence of co-founder Richard Harvey, is poised, at the time of writing, to perform the new album in the Union Chapel.

In honour of the new release I thought it might be interesting to attempt to resurrect what is the first recording I ever made of the band (I was their sound engineer in the studio and on the road from 1974–5, culminating in the recording of the Raindance album across Midsummer 1975, which I engineered and co-produced). This was a recording of the live performance given at the Old Vic on 14 July 1974 – the first and, I believe the only, rock concert ever to have been held at the Old Vic or hosted by the National Theatre. Gryphon had recently been commissioned to write the music for Peter Hall’s National Theatre production of The Tempest, which had premiered on March 5, and had recorded their second album, Midnight Mushrumps (a reference to Prospero’s speech, 5.1.39) including a suite based on the music for the play, with Dave Grinsted at Chipping Norton Studios in the Cotswolds.

The Old Vic performance was right at the start of my involvement with the band and I was yet to be responsible for their sound live or in the studio. However for the occasion of the Old Vic performance I was able to obtain a Teac 3340 4‑track recorder and situated it beside the mixing desk on the balcony. I had a pair of AKG D‑202s, excellent all-round dynamic mics, arranged in a coincident pair as close to the centre of the balcony as I could get, and recorded these on one pair of tracks on the Teac; and in addition I put a stereo feed from the board on the other two tracks. The resulting 4‑track tape gave me a clean feed of the PA mix, with the addition of audience reaction and ambience from the room mics – particularly effective on the percussion. However as we were on the balcony there was a delay between the PA feed and the room mics, so when I mixed-down the 4‑track to stereo I put a delay on the PA feed tracks to bring them into sync with the room mics. This also gave me the opportunity for a little fun, as I could vary the delay slightly to give a slight flanging effect on tracks like Estampie, which Richard Harvey refers to in the intro as “a mediæval one-bar blues”, an effect which had been used on the original album recording for a similar purpose.

The disadvantage of the PA feed was that it included a bass DI run at considerable level, and as a result, Philip Nestor’s bass-playing features prominently in the feed. So much so, in fact, that the bass causes some intermodulation distortion with other instruments, rendering some of the pieces sadly virtually unusable. However with some judicious use of EQ around the 80–200Hz mark the bass can be quietened-down enough for a reasonable balance to be achieved in many cases.

Sadly the original 15in/s mixdown master of this recording is lost, and believed to be in Los Angeles. However I made a cassette copy of the three reels which I hung on to. They were BASF Chrome cassettes and I recorded them with a Dolby B characteristic on a machine that I had evidently been able to set the Dolby level on correctly as the results are quite respectable. For these experiments I transcribed the cassettes from a Technics M260 kindly provided by Duncan Goddard, who is a highly talented restorer of vintage analogue recorders, having previously supplied my trusty ReVox PR99 and A77.

I digitised the audio via a Focusrite Scarlett interface and brought it into Adobe Audition, my DAW of choice for stereo audio production. I cleaned up the noise floor with Audition’s built-in noise reduction tools and a couple of Wave Arts restoration plug-ins, using the Audition parametric EQ to restrain the bass end. Here’s an example of the results: the mix of Estampie referred to above. And I hope you like it.

August 20, 2018 Comments Off on Restoring an Ancient Gryphon

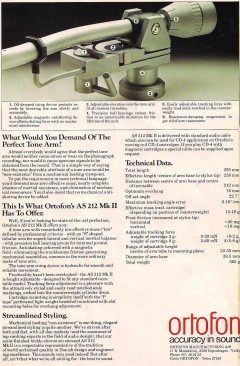

Inside a Telefunken S600 Belt-Drive Turntable

I hadn’t intended to end up with more than one turntable, but I now have no less than four, all of which work. The most recent one I’ve been working on is a Telefunken S600, which turns out to be an exceptionally well-designed turntable with a number of ingenious bells and whistles.

As I detailed previously, I wanted to replace the standard tone arm on a Lenco L75 turntable with an Ortofon AS-212. These are found (amongst other places) on Telefunken S600 belt-drive turntables, so I sourced one from Germany to steal the arm — but fellow members of internet groups I belonged to were horrified that I would do this to an actually rather nice turntable. So I relented, and one of my correspondents found a New Old Stock AS-212 that I duly installed on the Lenco.

Meanwhile, the S600 arrived from Germany, in rather a sorry state. Despite being very well packed, the plastic cover was cracked almost in two and the back of the arm had gone missing along with the counterweight. The well-known international shipping company had both damaged it and mis-delivered it: the incorrect recipient had opened it and lost some of the bits. So when it got here I wouldn’t have been able to pinch the arm for the Lenco anyway.

But now I had learned that these decks were actually quite good, I decided to attempt to repair it. And if it was actually a good deck, I might want to use it as my main deck — in which case it needed a modification to run at 78rpm.

Fixing the arm

The big problem was the arm itself. This consists of an S‑shaped arm tube with a bearing housing on the end made of some mysterious hard rubbery material. A small tube containing two sets of four 1.2mm ball bearings goes transversely through the housing and is held in place by two pointed set-screws that have to be set up exactly right so that the arm sits centrally in its holder with freedom to move up and down but with no play. The housing has an extension stub on the back, and on to this mounts a threaded tube on to which the counterweight screws. In this case, the stub had snapped off the back of the bearing housing and with it had gone the threaded tube and counterweight.

There were several possible solutions. Replacement bearing housings are available on eBay from time to time, made either of Delrin or brass. The threaded tube is available too. I could replace the bearing housing (get the housing off the arm tube, push the bearing tube through and put it into the new one, add the threaded tube and reattach the arm). I could consider getting a threaded tube and fitting something inside it that I could push into the back of the bearing housing and glue it in place. I got the bits to do the latter, namely the threaded tube and some metal-filled resin. But the procedure seemed a bit dodgy, frankly. Would it stay stuck? Would the resin go where it shouldn’t? Would it look decent? I looked for a new bearing housing instead, but found only brass ones, which seemed like overkill to me — the black Delrin ones didn’t seem to to be available at the time. But then a contact of mine kindly came up with a solution: a complete replacement arm with the arm tube, bearing housing (with bearings) and threaded tube — plus an original counterweight. Excellent. All I had to do was to fit the arm — and send the old one back to him.

The replacement arm assembly duly arrived, and is shown here. The supplier very kindly taped up the bearing housing so the balls couldn’t fall out (I had obtained some spares in case they did, but I didn’t need them). First I needed to de-solder the arm leads, which meant getting the turntable out of its plinth.

This simply required undoing three screws. Telefunken really designed these turntables thoughtfully. You lift up the turntable, turn it vertically and then you can slide it into grooves in the plinth where it stands safely so you can work on it.

Here’s the innards of the turntable, and there are a lot of things to talk about here in due course. Click on the image to see it up close. I de-soldered the arm wires (they attach to a terminal strip bottom right next to the muting relay) and then put the deck back in the plinth. I had armed myself with a pair of tiny circlip pliers with 1mm prongs to fit the lock-nuts surrounding the bearing set-screws (one set of both on either side — you can see them in the broken original arm image above) and now attempted to loosen them. Pleasingly they loosened surprisingly easily and I was then able to unscrew the set-screws enough to carefully lift the arm out. Thankfully the little ball bearings stayed in there too. So I taped it up ready to send off. The new arm went in with surprisingly little trouble too. First I led the wires through the arm column by putting them into a drinking straw and pushing that down the hole in the centre of the column. Then, using a business card as a feeler gauge to centre the arm in the mounting, I held the arm in place and gently tightened the screws. Then holding the screw in position with a screwdriver I tightened the locknut, first on one side, then the other. It took about three goes to centre the arm successfully and lock the screws in place, but the result was an arm that exhibited negligible resistance when moving in its bearings. Exactly what was required. This pic shows the new arm in place minus the counterweight.

Here’s the innards of the turntable, and there are a lot of things to talk about here in due course. Click on the image to see it up close. I de-soldered the arm wires (they attach to a terminal strip bottom right next to the muting relay) and then put the deck back in the plinth. I had armed myself with a pair of tiny circlip pliers with 1mm prongs to fit the lock-nuts surrounding the bearing set-screws (one set of both on either side — you can see them in the broken original arm image above) and now attempted to loosen them. Pleasingly they loosened surprisingly easily and I was then able to unscrew the set-screws enough to carefully lift the arm out. Thankfully the little ball bearings stayed in there too. So I taped it up ready to send off. The new arm went in with surprisingly little trouble too. First I led the wires through the arm column by putting them into a drinking straw and pushing that down the hole in the centre of the column. Then, using a business card as a feeler gauge to centre the arm in the mounting, I held the arm in place and gently tightened the screws. Then holding the screw in position with a screwdriver I tightened the locknut, first on one side, then the other. It took about three goes to centre the arm successfully and lock the screws in place, but the result was an arm that exhibited negligible resistance when moving in its bearings. Exactly what was required. This pic shows the new arm in place minus the counterweight.

The turntable was now back more or less to its original specification, give or take. I ran it up and found that it reached 33 or 45 very quickly considering the weight of the beautifully-balanced platter, and the speeds were rock solid. The touch buttons for speed and stop all worked as intended and the speed control trimmer knobs worked well. I hadn’t even had to replace the electrolytic capacitors. (If I had needed to, the information required – along with lots more about these turntables – is here.)

The turntable was now back more or less to its original specification, give or take. I ran it up and found that it reached 33 or 45 very quickly considering the weight of the beautifully-balanced platter, and the speeds were rock solid. The touch buttons for speed and stop all worked as intended and the speed control trimmer knobs worked well. I hadn’t even had to replace the electrolytic capacitors. (If I had needed to, the information required – along with lots more about these turntables – is here.)

Bells and whistles

This turntable has several bells and whistles. The main ones are to do with the arm lift. This can be actuated manually with the lever — there is a Bowden-style cable from the lifter lever to a fluid-damped dashpot under the arm rest. There is a locking arrangement that only lets the lever lock in the down position if the turntable is under power, and if you hit Stop it lifts up the arm (and when the arm is lifted, incidentally, the relay mentioned earlier mutes the audio).

It is also intended to lift the arm at the end of a side. This is accomplished in a rather ingenious way. Look at the photo of the underside above and you’ll see that there is a slotted copper arc just to the left of the motor control board. This is attached to a very lightweight arm that is linked to the tonearm, and swings across under the turntable as the arm tracks a disc. Just next to the copper arc (which we’ll come to in a moment) is a V‑shaped cutout. This is the clever bit. When the arm reaches the end of a side, that V passes between a big frosted bulb (just below the centre of the image) and a light-dependent resistor, shading it from the light. (Why the V I don’t know: it will mean that the illumination drops slowly rather than at once. Why?) This is detected and hits Stop on the turntable, which also powers-down a solenoid to release the arm-lifter to lift the arm. That is what is supposed to happen, but unfortunately it didn’t work. In fact it is a little surprising that the turntable would run without holding a button down. The bulb had expired.  It looks very much like a W5W auto bulb but it’s only supposed to take 100mA. Luckily there are W5W replacement LED bulbs that run that kind of current so I popped one in. On power-up this duly illuminated, and now the arm lifted and the turntable stopped somewhat before the arm reached the end of its travel, corresponding to just before the locked groove on a disc.

It looks very much like a W5W auto bulb but it’s only supposed to take 100mA. Luckily there are W5W replacement LED bulbs that run that kind of current so I popped one in. On power-up this duly illuminated, and now the arm lifted and the turntable stopped somewhat before the arm reached the end of its travel, corresponding to just before the locked groove on a disc.

While we are looking under the turntable, let’s look at what that copper arc does. As the arm swings, it stops the light from another, smaller bulb, directly to the right of the main bearing, from falling on the end of a light-pipe — that little clear tube going up to the top of the deck and past the orange string (which is the interlock between the power switch and the arm lifter). It ends in a little bezel on top of the deck. The light is thus visible from above the deck except when it’s obscured by that copper arc — which means the light is visible when the arm is beyond the platter and when the light can shine through the three slots in the arc, which correspond to the edges of a 7in, 10in and 12in disc. So basically it tells you where to put the arm for the start of a disc.

I thought the drive belt a little stretched and worn so obtained a replacement from thakker.eu (for the S500, a simpler version of this turntable, but with the same motor/subplatter arrangement).

A speed mod

With the deck returned to its original specification, next came the modification I wanted to perform — to get it to run at 78rpm as well as 33 and 45. I had asked about this in the Vinyl Engine online forum and a gentleman had kindly looked at the circuit diagrams I had found and suggested how to do it. It turns out that this design of turntable was actually licensed from Philips, though Telefunken made some extensive subsequent modifications. It’s a DC servo-controlled motor arrangement, and in some of the original Philips models using the same motor and control board design, the turntable can actually do 78 rpm right out of the box — so there was no reason why this shouldn’t work.

The answer, my respondent suggested, was to put a resistor across the main 45rpm speed control resistor (R133) to reduce its value, then use the 45rpm speed knob to fine-tune the speed to 78. I decided to go a little beyond that and put a trimpot in series with the fixed resistor so that I could set the speed to 78 with the 45rpm speed control knob in the centre position as it was for 45, and not have to adjust anything unless I wanted to run at a special speed like 80rpm for example. It took some experimentation to get the values right: eventually I used a 47k? fixed resistor in series with a 10k? trimmer. I soldered these to a miniature DPDT toggle switch that I mounted in the lower right-hand side of the plinth, with a hole to access the trimmer, and a LED and series resistor, powered from the lamp supply, on the other poles of the switch so a red light comes up when you select 78. And it works beautifully — here’s a Conroy music library 10in 78 spinning at the right speed!

Finally, I replaced the audio output cable, adding a pair of Neutrik phonos in place of the original 5‑pin DIN, and ran a chassis ground wire along the audio cable with a spade connector on the end. In fact this is of limited use as the mains on the turntable goes via a double-pole switch straight into a double-wound transformer: the chassis and all the audio grounds are connected together and have no connection to the mains side. Untangling this to provide separate audio and chassis ground turned out to be a real pain — to retain the muting relay function would have required serious rewiring — so I left well alone, and in fact it works fine, and the chassis can be connected to mains earth if desired.

The turntable has a cast stroboscope at the edge with its own neon lamp, but of course it doesn’t include 78, so I printed out an image of an old Garrard strobe for now and that works fine — maybe I’ll pick up one of the Lenco metal ones at some point.

In operation

So, now to try the turntable out. I mounted the Shure M97xE in a skeleton headshell originally acquired for my TT-100 and set it up for 16mm overhang (tricky as you can’t move the arm to the centre spindle: I cut a piece of wire to length as a measure) and lined it up with a cartridge protractor: it lined up perfectly. Setting the tracking weight and anti-skate accordingly, I played a tone disc with the arm at different positions and the waveform and sound were clear and undistorted throughout. I then played some music, and found this under-recognised turntable, believed by many to out-perform many other belt-drive turntables of the period such as those by Thorens, was a marvellous performer, delivering an excellent, open and stable sound just as I would like it.

So, now to try the turntable out. I mounted the Shure M97xE in a skeleton headshell originally acquired for my TT-100 and set it up for 16mm overhang (tricky as you can’t move the arm to the centre spindle: I cut a piece of wire to length as a measure) and lined it up with a cartridge protractor: it lined up perfectly. Setting the tracking weight and anti-skate accordingly, I played a tone disc with the arm at different positions and the waveform and sound were clear and undistorted throughout. I then played some music, and found this under-recognised turntable, believed by many to out-perform many other belt-drive turntables of the period such as those by Thorens, was a marvellous performer, delivering an excellent, open and stable sound just as I would like it.

The only problem I have now is what to do with all these turntables. I really don’t want to get rid of either the Lenco or the Telefunken and I think the former will end up on the main system downstairs while the Tele stays in my studio for transcription (alongside the excellent Technics SL‑7 linear tracker, which doesn’t do 78).

November 3, 2016 Comments Off on Inside a Telefunken S600 Belt-Drive Turntable

Modifying an Idler Turntable

One of my activities is transferring archive music library master tapes to digital, so they can be made more widely available again. This is not always straightforward, and it’s sometimes necessary to transfer excerpts from disc if the master tape is damaged in some way. To do this requires a decent vinyl playback system. This article is about how I put one together.

Sometimes there are problems with the old tapes — such as oxide or backing shedding, and in particular when the backing binder becomes sticky and stops the tape passing through the machine. Another issue is the adhesive used in splicing tape becoming sticky (although it is specifically supposed not to) and this can result in oxide fragments being pulled off the front of a track resulting in dropouts. And unlike the solutions for sticky binder and shedding (such as baking the tape or running it through a white spirit or isopropyl alcohol-soaked pad) sticky splicing tape causing damage is difficult to avoid, even if winding very carefully.

On more than one occasion, problems like this, or major dropouts, tape damage and other issues, mean that a (usually short) section of the master tape is unrecoverable. The solution, then, is to try and find a copy of the library disc pressed from the master, capture the appropriate section, match it in level and other characteristics and then edit it into the version transferred from tape.

A better vinyl playback system

To do this effectively requires a decent record deck, and while the unit I’ve had for some time — a Numark TT-100, essentially a DJ turntable — does a good workmanlike job, and has the benefit of 78rpm (which is sometimes necessary) as well as 33 1/3 and 45, I though it worth spending a bit of time and money acquiring a superior vinyl playback system.

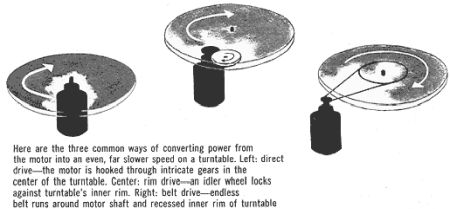

There are basically three types of ways in which the motor can drive the platter in a turntable: Idler Drive, Belt Drive and Direct Drive. They’re illustrated in the diagram above. It should be noted that there is often more than one way of implementing all three of these methods: Direct Drive — often found in DJ turntables — can involve the actual platter being part of the motor, rather than requiring the “intricate gears” suggested above; with Belt Drive the belt may go round the entire platter and not a sub-platter; and in the case of idler drive the idler may be horizontal (as shown — Garrard used this) or vertical (as in the Lenco designs).

The Lenco L75

I decided on an idler design as these are highly-regarded for their sound quality. While it would have been nice to have, say, a Garrard 401 transcription turntable, this was well out of my price range and I settled instead for a Swiss-made Lenco L75. I found one for a good price and a relatively short drive to Norwich. I have never actually owned one of these before, though I remember one from the school music room, many years ago (they were common in educational institutions).

As soon as I got it home I reviewed it visually, and all looked good, so I powered it up and it ran fine, solidly at each speed. It had a rather cheap and nasty original plinth that (still) needs to be replaced with a proper, solid one. These decks perform best without the benefit of the springs provided supporting it in the plinth, so I removed them.

Updates: V‑blocks and wiring

Then I looked at the so-called “V‑blocks” in the arm suspension. NOTE that I didn’t use the original Lenco arm in the end, but this info may be helpful if you are. The arm has a knife-edge bearing that allows it to swing up and down. The knife edge, attached to the arm tube, rests in two V‑shaped blocks, one either side, and they are notorious for degrading. Sure enough, mine had decayed into solid lumps that looked like yellowed teeth. I carefully scraped them out, cleared the holes, and replaced them with a pair of “desmo” V‑blocks sourced from eBay. The whole operation was remarkably straightforward.

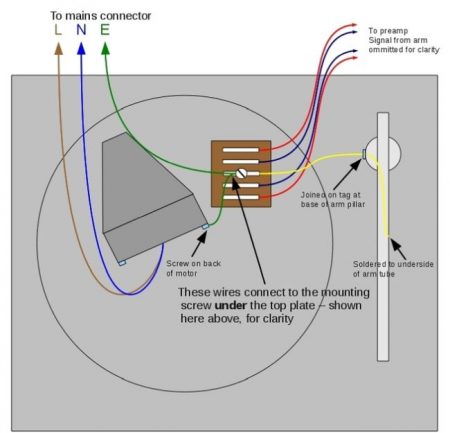

Next I reviewed the wiring. The audio cabling centres around a terminal block on the underside of the deck plate and here the wires from the tonearm headshell meet the shielded cables going to the outside world. The left and right signals and their respective ground leads need to by electrically separate from the chassis ground (a yellow wire also leading out of the plinth): in my case they were, but I replaced the coax with modern cable and the DIN plug on the end with two gold-plated phonos. The metal body of the arm is grounded to the chassis.

On the mains side, the circuit is simple: Live and Neutral come in, one leg goes via a switch to one side of the motor and the other side goes to the motor. This might have been fine 40 years ago but today, with old electrical systems, we probably want a better approach. The suggestion in the Lenco Heaven forum — where all the experts on the subject of these turntables hang out — is to follow the wiring shown below, drawn by Stephen Clifford:

Not shown above is the fact that the yellow (chassis ground) lead is extended out of the plinth to be connected to the appropriate connector on a phono preamp if required.

Impossible hum

Having carried out all the re-wiring, I installed a cartridge and ran it up. And it hummed, badly. Now you do not need the yellow lead connected to ground on the phono preamp and the ground connected in the mains plug as it will cause a hum loop, but in this case I could not get the hum to go away, whatever I did. I tried cleaning the headshell and arm contacts, different earthing schemes, different cartridges and even different preamps, but to no avail.

It seemed likely to me that the problem lay in the wiring to the headshell connector but this seemed fairly hard to address. In addition (and no doubt purists will hate me for saying so), I found the original arm rather clunky. So, even though I had carried out the task of replacing the V‑blocks et al, I decided to replace the tone arm.

The Ortofon AS-212 as a replacement arm

There are only a couple of tone arms that will slot more or less straight into a Lenco, ie they are the right length etc to fit. The one that appealed to me was an arm made by Danish manufacturer Ortofon (famed for their pickup cartridges) the AS-212. But where to find one? Hunting around netted me a gentleman in Germany selling a Telefunken S600 deck — these were fitted with this arm — at a good price.

There are only a couple of tone arms that will slot more or less straight into a Lenco, ie they are the right length etc to fit. The one that appealed to me was an arm made by Danish manufacturer Ortofon (famed for their pickup cartridges) the AS-212. But where to find one? Hunting around netted me a gentleman in Germany selling a Telefunken S600 deck — these were fitted with this arm — at a good price.

Sadly, when it arrived, the rear of the arm had disappeared and the lid of the turntable was cracked — a result of the shipping company mis-delivering it and the erroneous recipients opening it.

Not only that, when I mentioned my intentions on a Facebook group I belong to specialising in vintage equipment, they were horrified. The Telefunken S600 was an excellent belt-drive deck, they said, probably out-performing the Thorens decks of the time, and should not be vandalised and left ‘armless’. So I decided to repair it, and see if I could find a spare AS-212 arm for the Lenco, then keep the one I preferred and sell the other. The Telefunken story is for another article.

Immediately up came an offer on the Vinyl Engine forum of a complete AS-212 arm, boxed: a replacement arm for a Telefunken. At the same time I received an offer of a replacement armtube, bearing and counterweight. I could use the former on the Lenco and the latter to repair the Telefunken.

Preparing the arm for fitting

The new-old-stock complete AS-212 assembly duly arrived, and I acquired a mounting base for the new arm to fit the Lenco deckplate hole — the Ortofon is a different diameter and thus needs a different fitting. These are available on eBay: I bought a silver-coloured one.

Before fitting to the Lenco, the new arm needed some dismantling. I decided to use the Lenco arm lifter — pretty much obligatory, in fact, with an AS-212 designed for an S600, as the Ortofon arm comes with an oil-damped lifting cylinder with just a bottom pin that is supposed to fit into the S600 lifter mechanism, a clever Bowden-style cable arrangement: thus it does not include a complete lifter system. So I removed the lifter cylinder and arm rest, leaving a 10mm hole in the body of the arm, which I decided to fill with a suitably-sized circular bubble spirit-level, secured with the existing set-screw. Adjacent to it in this picture is the AS-212’s natty no-contact magnetic anti-skate system. The little hole formerly took a pin on the lifter to stop it rotating. I found a use for it later.

I also removed the arm clip from the AS-212 (the rod to the left of the above image is the back of it) so as to use the Lenco one, which is the correct diameter to hold the arm securely.

Next step was to mount the arm column in the new base. This was easily done. I set the height up by attaching a cartridge and adjusting the height so that the arm was horizontal with the stylus resting on a disc. I lined up the body of the arm to be parallel to the edge of the deck-plate and it looked great. I tightened the set-screw and there it was.

A few modifications

An initial problem was that the arm wiring was not as long as the original Lenco, so I moved the audio connection tag strip to somewhere nearer to the arm so it reached, and under the deck plate instead of on top.

This picture also shows the revised power wiring mentioned earlier. I made a new hole in the plinth for the audio cables to exit so that they didn’t run parallel to the power cable.

The Lenco lifter actuator lever is quite long, and actually fouled the arm when at rest, so I shortened it. Actually, I was going to bend it outwards but the top bit snapped off. Ooops. It’s still easy to reach and use: a short piece of black heatshrink tubing and it looks the same as the original, but shorter.

The biggest challenge was getting the lifter to work. The Lenco lifter arm is quite deep, and when lowered rested on the top of the Ortofon platform long before the stylus was able to reach the record. I thought this could be solved simply by shortening the lifter arm to avoid the edge of the platform, but this was a Bad Idea as the arm could drop down and hit the deck plate between rest and the start of a disc, and tended to fall off the end of the lifter. The solution instead was to file the underside of the end of the lifter arm where it overhung the platform to about half its depth. This allowed the lifter to drop far enough to allow the stylus to reach the record. All the elements of the arm are able to be adjusted for height: the lifter arm, the arm rest, and of course the arm column.

It’s worth noting that there is a small caveat here. The Lenco arm rest, which I’m using, allows the arm to be unclipped by moving it vertically. It is possible, once unclipped, for the arm to swing outward, whereupon it will fall off the lifter arm and could drop down and clout the cartridge on the power switch or the deck plate itself. I made this impossible by inserting a thin rod into a hole left by part of the original AS-212 lifter mechanism and bending it over and above the arm to stop this from happening. You can see the hole in the close-up of the bubble level a couple of images up. While I was at it, I added a cut-down self-adhesive foot to the right-hand front of the platform so that the arm couldn’t drop if it went backwards. Another approach would have been to reinstall the Ortofon arm clip, which opens towards the turntable and is thus less likely to allow the arm to go backwards. However this would require removing the Lenco arm-rest, leaving a hole in the deck plate.

Next I needed to mount the cartridge more accurately. The AS-212 needs a 16mm overhang — ie if you swing the arm across to be over the central spindle, the stylus should be 16mm to the left of its centre. This proved to be quite difficult to do: the slots in the headshell only just allowed it with the cartridge as far back as it would go. But it worked, and I was also able to set up the null points successfully with a protractor, with the cartridge parallel to the groove at both points. The correct way of fitting the cartridge is to use the two threaded rods on the underside of the manual lifter prong, but in my case, although I have several Ortofon headshells, none of them would actually hold the Shure M97xE, either because they were too long, too short or there wasn’t room for the nuts. So I mounted the cartridge with a pair of bolts and fitted the manual lifter separately (see below).

Playing some records

With that done, I carried out a final check of the settings, including: checking that the arm really was horizontal while playing and thus the Stylus Rake Angle was correct (I think this is a better way of looking at it than by addressing the Vertical Tracking Angle, and I don’t have a microscope); setting up the tracking weight for my Shure M97xE; and adjusting the AS-212’s elegant magnetic anti-skating setting.

With that done, I carried out a final check of the settings, including: checking that the arm really was horizontal while playing and thus the Stylus Rake Angle was correct (I think this is a better way of looking at it than by addressing the Vertical Tracking Angle, and I don’t have a microscope); setting up the tracking weight for my Shure M97xE; and adjusting the AS-212’s elegant magnetic anti-skating setting.

And then I played a record for the first time — but not a terribly exciting one. It was the B‑side of a KPM Music Library test pressing of pieces by Richard Harvey, consisting solely of a 1kHz tone. I was able to listen to the tone quality at various points across the disc and was very pleased with how pure the tone was at all points.

Then to play some actual music: the content side of the same disc. I was immediately very impressed with the wide frequency range apparent on playback, and a good tight feeling to the bass end. The overall sound was very clear, clean and detailed, and the stereo imaging nice and stable. Excellent.

My view is that this is an exceptional combination of arm and deck and I am very pleased with the results so far, though I need to give it a lot more critical listens. But in theory, all that’s needed now is a new plinth that does the deck justice.

I have, incidentally, kept all the Lenco bits I’ve removed, included spares of items I modified (eg the lifter actuator lever and the lifter arm) so that if it ever needs to be restored to its original spec, this can be done.

October 11, 2016 Comments Off on Modifying an Idler Turntable

Gryphon At Bilston

Just over a year after seeing the re-formed Gryphon at The Stables near Milton Keynes, I was lucky enough to catch them live at the Robin 2, a cavernous West Midlands venue somewhat reminiscent of somewhere like the Station Inn in Nashville, in one of a short series of live gigs culminating in a performance at the gorgeous Union Chapel. Sadly I couldn’t make the latter, but it is being professionally video-recorded so hopefully we’ll all be able to see it at some point.

A Brief Historie

For those of you who don’t know the band — and if you do, you can skip to the section headed Robin 2 below — Gryphon was formed in the early 1970s and was a kind of crossover act merging mediaeval and Renaissance music and instruments, with bassoon, flute, guitars, percussion (and ultimately drums) and bass for an effect that varied from folk music to rocked-up Early Music to something approaching Prog Rock. A truly marvellous combination, I assure you, as any of the five albums produced in the 1970s (and all still available, along with various collections of previously unreleased tracks and broadcast performances) will attest.

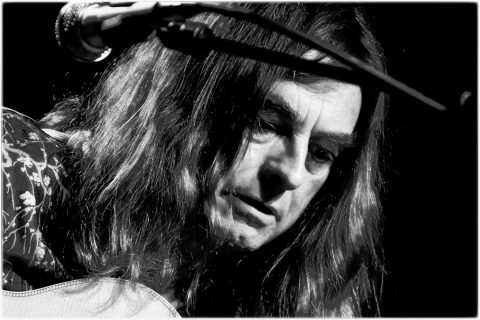

At the heart of the band were two people I went to school with (albeit two years below me), multi-instrumentalist Richard Harvey and guitarist Graeme Taylor, one or other or both of whom, often with Brian Gulland, penned much of the original material that appeared on the albums such as the characteristic intricate instrumental suites (Juniper Suite on their eponymous first album, for example, being credited Taylor-Harvey-Gulland) and longer works while Taylor wrote often delicate, finely-wrought instrumentals and songs with wildly punning and semi-obscure lyrics. The other band members contributed their own material too, to great effect, and combined with their settings of traditional songs and dances, Gryphon was entirely unique. I was lucky enough to tour with the band for a year as their sound engineer, live and in the studio (1974–5, including US and UK tours supporting Yes as well as college gigs, culminating with the recording of their fourth album, Raindance, which I also co-produced).

The band was effectively wiped out by the changes in British popular music in the mid-70s that resulted in instrumental virtuosity — or indeed almost any level of musical ability above that of a member of the audience — being deprecated. Thankfully the albums never really went away, and even the unreleased tracks appeared on Collection CDs in due course (including several from Raindance, which was essentially cut to ribbons by the record company, omitting a few gems).

Reformation

Everything seems to come around again these days, and over 30 years after their final live appearance, the band re-formed in June 2009 for a sold-out reunion concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on London’s South Bank featuring the original core membership of Richard Harvey (woodwinds, keyboards), Brian Gulland (woodwinds, keyboards, vocals), Graeme Taylor (guitars, vocals), and Dave Oberlé (percussion and vocals). They were joined by Jon Davie — the bass-player from the band’s fifth album, Treason — and new arrival, talented multi-instrumentalist and veteran music library/film composer Graham Preskett on a varied collection of keyboard and stringed instruments.

Everyone hoped that the one-off reunion would be followed by a tour, but it was not until 2015 that this actually got off the ground with a relatively short series of gigs — all of which were extremely well attended and showed that the band had lost none of its vigour and originality. Indeed, the presence of Preskett at last made it possible to perform works that had been impractical to play live previously, such as Juniper Suite.

The hope was that there would be additional dates in 2016 and this indeed came to be, but, it transpired, without the presence of Richard Harvey, who announced in the Spring that he would be leaving the band due to a cramped schedule and to pursue his own multi-faceted career. And indeed it is, with a major tour with Hans Zimmer and many other activities on the horizon.

Robin 2

(Most of) Gryphon at Bilston, August 14 2016. L to R: Keith Thompson, Dave Oberle, Graeme Taylor, Rory McFarlane, Brian Gulland. Where’s Preskett? Photo by Paul Lucas

As a result, the band that has been touring in 2016 has some changes in lineup. Preskett is in there — he is a major asset — and on bass we find Rory McFarlane, a talented session musician and composer who has also plenty of band experience with Richard Thompson. It would be silly to say that “Richard Harvey’s place in Gryphon has been taken by Keith Thompson”, because Keith is an extraordinarily talented Early Music woodwind specialist in his own right with a history going back to the 1970s and including the exceptional City Waites: he brings to the band a level of talent and expertise that is extremely impressive. The combination of musical skills represented by this incarnation of the band is unsurpassed and delivers the instrumental fireworks we might expect from a group of musicians who are all at the peak of their powers.

And thus, finally, to the Robin 2 gig. The performance fell into two sets and followed a similar structure to the gigs of 2015, with primarily pieces from the first album in the first half — Opening Number to begin with, followed by Kemp’s Jig, The Astrologer (with an amusing contest of vocals between Gulland and Oberlé), and the aforementioned Juniper Suite. Next up was The Unquiet Grave, to which Brian Gulland gave an interesting introduction, mentioning Vaughan Williams’ Five Variations on Dives and Lazarus, which employs the same tune, while The Unquiet Grave itself is often heard with a different melody. I always wondered about that… The set was rounded off by Dubbel Dutch from the Midnight Mushrumps (second) album and Estampie from the first.

Later material permeated the second set, leading off with a medley from the third album, Red Queen to Gryphon Three with its chess references. Second up was the Graeme Taylor-penned and atmospheric Ashes, originally removed from the fourth album, Raindance, to my distinct annoyance, and one of my favourites of the band’s songs. And they very kindly gave me a shout-out for the track, which was most kind! The performance was complete with birdsong: when we recorded the track originally, in the hot midsummer of 1975, I recorded Brian Gulland’s vocals outside in the open with a stereo pair of mics, with him standing far enough away that I could crank up the gain and capture the natural birdsong. Further pieces in the set included more from the first album, some dances originally written by High Renaissance German composer Michael Praetorius for his enormous set of dances known as Terpsichore (and which, we should note, are yet to be recorded, hint hint..), Lament from the third album and rounding off with the thunderous romp that is Ethelion from the second album. An encore consisted of a very amusing combination of tunes leading off with Le Cambrioleur est dans le Mouchoir, (a strange little piece from Raindance, co-written by Taylor and bass player of the time Malcolm Bennett) followed by a touch of Preskettised Gershwin and then Tiger Rag.

The overall performance was excellent and particular credit needs to be given to Keith Thompson, new to the band and with only one previous live performance with the band under his belt at this point. Gryphon has an unusual, if not actually unique, combination of what would traditionally have been called “loud” and “soft” instruments. In addition to being difficult to get a live sound balance on, as I know from my own experience, the stage monitoring is particularly tricky, and Keith was sandwiched between Graham Preskett on one side and Graeme Taylor on the other, neither of whom are likely to have been particularly quiet in the monitors. Despite this, and a cavernous hall with a huge and venerable PA that was really designed for out-and-out rock bands that swallowed him a little from time to time, Keith’s performance came across as lively and exciting and full of virtuosity.

Keith and Brian Gulland therefore handled the woodwinds ancient and modern, in the same way as Harvey and Gulland would have done in earlier times; but in addition the keyboard axis was between Brian and Graham Preskett, with Preskett also contributing fiddle and other stringed instruments. The multi-instrumental interplay between the three of them was one of the most interesting aspects of this new lineup and I am sure that they will only become even tighter and more dazzling as they work longer together. Meanwhile, Graeme Taylor’s guitar expertise seems only to increase every time I hear him — and while we’re on the subject of Graeme, don’t miss the latest release from his ‘other’ band, Home Service, whose new album A New Ground is definitely worth a listen. Brian Gulland, meanwhile, continues his endearing hirsute antics on stage, and on this occasion handled a good deal of the introductions, and in some cases — The Unquiet Grave referred to above for example — we learn more about the numbers, which is a good thing in my view, as long as it’s not too extensive (which it wasn’t).

Dave Oberlé was excellent throughout, not only on drums/percussion but on vocals too, where his style suits the material down to the ground. From where I was sitting, I couldn’t actually see bassist Rory McFarlane but I could certainly hear him, providing a solid bottom end to the sound and always spot-on with timing. You can’t really think of Gryphon as having a “rhythm section” as such, as Oberlé’s role is generally more percussion than drums, but McFarlane underlines the importance of good lively yet solid bass playing with this material.

Overall, then, an exceptional performance and one that bodes very well for the future, as the band evidently intend to stick around. As I noted at the top, the Union Chapel gig is being video recorded, and I hope to see that released at some point. And there is even talk of an album in the works — 40 years after the last one. Excellent going.

September 12, 2016 Comments Off on Gryphon At Bilston

Gryphon at The Stables

Wednesday May 13th saw a performance by Gryphon at the Stables near Milton Keynes. The gig was one of a relatively brief series of performances under the banner “None the Wiser” that the band, originally active in the 1970s, re-formed to give.

The personnel on the tour represented a fair approximation to the original lineup of Brian Gulland (bassoon, Renaissance woodwinds, vocals and a touch of keyboard), Jon Davie (bass), Dave Oberlé (percussion and vocals), Graeme Taylor (guitars), and Richard Harvey (keyboards, woodwinds, mandolin, clarinet, Renaissance woodwinds, dulcimer, ukulele, flute), augmented by an additional talented multi-instrumentalist and composer in the form of Graham Preskett (keyboards, violin, 12-string guitar, viola).

The tour culminated with a performance at the Union Chapel in London, which I would love to have attended: the picture above (by Julian Bajzert, used by permission) was taken there (the band appears almost in the order listed above, but with Richard Harvey far right).

The Stables, not a location I’ve visited before, is an impressive venue, although perhaps best suited to theatrical work. The stage layout required the PA to be placed perilously close to the band – and to Richard Harvey in particular – which mean that a number of high-gain mics were pointing more or less directly at the PA. Speaking from experience as Gryphon’s sound engineer (live and in the studio, during 1974–75) the band is tricky to mix at the best of times, with its unique combination of “soft” and “loud” instruments (as they would have been called in the Renaissance period) and a nearby PA no doubt made the mix at the Stables difficult in the extreme.

For those who have not encountered Gryphon previously, the band began in the early 1970s when Royal College of Music graduates Richard Harvey and Brian Gulland started as a duo playing traditional English folk with Renaissance and mediaeval tendencies. They were soon joined by guitarist Graeme Taylor and percussionist Dave Oberlé, and then by bass-players Philip Nestor, Malcolm Markovich, formerly Bennett, and finally (1975–77) Jonathan Davie.

Their first (eponymous) album, recorded in 1973 by Adam Skeaping on 4‑track in a tiny studio in Barnes, combined lively approaches to traditional songs flavoured with recorders and crumhorns — earning the band a “Mediaeval Rock” label — with some original material by Harvey.

Their first (eponymous) album, recorded in 1973 by Adam Skeaping on 4‑track in a tiny studio in Barnes, combined lively approaches to traditional songs flavoured with recorders and crumhorns — earning the band a “Mediaeval Rock” label — with some original material by Harvey.

The second album, Midnight Mushrumps (1974), featured a side-long suite based on the band’s music for Sir Peter Hall’s The Tempest at the Old Vic. The third, Red Queen to Gryphon Three (also 1974) featured a 4‑part suite theoretically based on a game of chess. This was followed by Raindance in 1975 and finally, following a move from Transatlantic Records to EMI/Harvest, Treason in 1977 – after which the band was sadly eclipsed, as were many talented British artists at the time, by so-called “new wave” artists who eschewed instrumental virtuosity.

I was lucky enough to work with the band as their sound engineer on the road and often in the studio, covering a college tour in mid-1974, the US 1974 and UK 1975 tours as support band to Yes, and culminating in recording and co-producing Raindance at Sawmills studios in Golant, Cornwall, across midsummer 1975.

I was lucky enough to work with the band as their sound engineer on the road and often in the studio, covering a college tour in mid-1974, the US 1974 and UK 1975 tours as support band to Yes, and culminating in recording and co-producing Raindance at Sawmills studios in Golant, Cornwall, across midsummer 1975.

There had always been hopes in several quarters that some incarnation of the band would get back together at some point, and the outfit has always had a loyal and extensive internet following. The albums are all available, along with additional albums covering BBC sessions and “lost tracks” (such as those we recorded for Raindance but were not allowed by the record company to include on the album — yes, it still annoys me). Hopes for a reunion were granted in 2009 with a one-off concern at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London which was exceptionally well-received, and saw the addition to the lineup of composer and multi-instrumentalist Graham Preskett for the first time.

The May 2015 tour, in preparation for some time, was relatively limited in extent but did enable a good many people to get to one of the very well-attended performances.

The first half of the Stables performance consisted primarily of pieces from the first album – kicking off, appropriately enough, with Opening Number, followed by the cautionary tale of The Astrologer with vocals by Oberlé in fine form, then an instrumental mélange of the traditional Kemp’s Jig and a mediaeval Estampie. This was followed by the band’s rendering of a personal favourite, also with vocals by Oberlé , The Unquiet Grave, an English folk song (Child Ballad 78) dating back to around 1400 in which a young man mourns his dead lover to a somewhat excessive degree, to which Gryphon add a particularly eerie middle section. Listeners to this piece with a classical background may note that the tune Gryphon use for this song (several tunes have been used traditionally) is also commonly associated with Dives & Lazarus (Child Ballad 56 – see Vaughan Williams’ variations on this theme).

Next up was a rendering by Graeme of his solo piece, Crossing the Stiles. All Graeme’s pieces for the band were tricky in one way or another and often complex, and hearing him perform this, one can only conclude that his guitar virtuosity has somehow increased over the years: his playing was exceedingly impressive.

It was followed by what I believe was the first live performance of Richard Harvey’s original composition from the first album, and the track that turned me on to the band all those years ago, when a friend played me this unknown track he had recorded from a John Peel programme: Juniper Suite. If it hadn’t been noticeable earlier in the set, it rapidly became clear here how beneficial the addition of Graham Preskett to the original lineup has been: the presence of extra keyboard resources, for example, freed Richard Harvey to focus more on his world-leading woodwind expertise, and made doing pieces like Juniper Suite live possible. Preskett, like Harvey, is also an excellent multi-instrumentalist, and the addition of violin and viola, for example, made quite an impressive difference at times, adding textures that were not previously part of the Gryphon sound but that fitted in exceptionally well.

During the course of the first set we also enjoyed some surprisingly ‘basso profundo’ vocals from Brian Gulland as well as his woodwinds and organ work. The ensemble piece Dubbel Dutch – a miniature suite in itself – from the second album closed the first half.

During the course of the first set we also enjoyed some surprisingly ‘basso profundo’ vocals from Brian Gulland as well as his woodwinds and organ work. The ensemble piece Dubbel Dutch – a miniature suite in itself – from the second album closed the first half.

The second half opened with a version of Midnight Mushrumps in all its album-side length glory, that often sounded pretty much exactly as it did when I mixed it live myself over 40 years ago.

The band then played one of my favourite ‘lost’ tracks, Ashes, which we originally recorded at Sawmills in 1975 for the Raindance album but which never made it on to the disc – and to my great surprise and pleasure, Brian very kindly dedicated it to me, which was extremely heart-warming. Thanks, guys! (The original recording is on the second Collections disc if you want to check it out.)

The set continued with a couple of excerpts from Red Queen to Gryphon Three – one based on Lament and then a medley of other themes from the album, all of which were expertly performed throughout, with plenty of Harvey recorder twiddly bits and some great bass-playing from Jon Davie, while Dave Oberlé fired off impressive rounds of percussion as appropriate. Indeed, the phrase ‘virtuouso performances’ can happily be applied to everyone in the band and to the whole set.

The set continued with a couple of excerpts from Red Queen to Gryphon Three – one based on Lament and then a medley of other themes from the album, all of which were expertly performed throughout, with plenty of Harvey recorder twiddly bits and some great bass-playing from Jon Davie, while Dave Oberlé fired off impressive rounds of percussion as appropriate. Indeed, the phrase ‘virtuouso performances’ can happily be applied to everyone in the band and to the whole set.

Encores included a marvellous new suite of rocked-up Renaissance dances of the kind for which Gryphon are perhaps traditionally best-known, outclassing even the likes of The Bones Of All Men and in this case relying quite a bit on Michael Praetorius’s Terpsichore, followed by a remarkable piece that, starting off from a certain Cambrioleur (Le Cambrioleur est Dans le Mouchoir, from Raindance), wove together several disparate threads including George Gershwin’s Promenade (Walking the Dog), and featured some exquisite clarinet work from Harvey, exchanging rapid-fire lines with Preskett, to end with a spirited interpretation of the very early 20th century jazz standard Tiger Rag.

Overall, I found it a magnificent and quite magical performance from everybody concerned.

Main image: Gryphon at Union Chapel, London, May 2015, by Julian Bajzert, used by permission. L to R: Brian Gulland, Jon Davie, Dave Oberle, Graeme Taylor, Graham Preskett, Richard Harvey

August 3, 2015 Comments Off on Gryphon at The Stables

An Electric Car (at least part of the time…)

There is a time when older vehicles start to become rather expensive to keep running, and with both our main vehicle, a 2001 Freelander, and our second car, a 2001 Focus that was a gift from friends, having had expensive or potentially expensive problems recently (and the Freelander has very nearly done the equivalent of going to the Moon), we thought it was time to consider something rather newer.

As we are trying to become rather greener in our lifestyles, an electric vehicle would be the ideal. But frankly, as it stands today, we can’t get the range from a ‘pure’ electric vehicle to do the sort of things we need to do (which includes a 200-mile round-trip once a week in my case, and more occasional long-distance trips, for example to Scotland). So the obvious thing to do was to look at hybrids. There is no way I could consider buying one new (and in fact I haven’t bought a new car since the 1970s, when someone wrote it off for me a few weeks after I bought it. I have this funny idea about not adding any new cars to the road…).

But what kind of hybrid? The obvious was one of the Toyota models. They’re built in the UK as far as I know, and they have a reputation for excellent build quality. But again, even a second-hand Prius was rather more than I had in mind pricewise. The next one down was a used Auris hybrid, and a very nice-looking car it is. A friend who knows the car said it behaved very well and was actually rather nippy.

However, although the Auris delivers good fuel efficiency – somewhere in the 75 mpg range I believe – it, like its bedfellows, is never a strictly “electric vehicle” – the wheels are driven by a combination of internal combustion engine (ICE) and electric motors. So you can never turn the ICE off. But while we needed a car that could do longer journeys (I would like ultimately to get us down to one car if at all possible), a lot of our driving is around Cambridgeshire and environs. That meant that another type of hybrid was actually more suited to our requirements: a PHEV (Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle).

In a PHEV, the wheels are always driven by electric motors. This is a Good Thing as the drive train is much simpler (and thus, one hopes, more reliable) and much more efficient than all that engine-and-gearbox stuff. And you just put your foot down and go. The vehicle is powered by batteries, and you recharge them by plugging it in. But, and it’s an important and positive ‘but’, when the batteries are exhausted, an on-board ICE kicks in, driving a generator to continue powering the drive for as long as there is fuel available, essentially turning it into the equivalent of a diesel-electric locomotive – a ‘series-hybrid’ if you like (though by some definitions, a ‘hybrid’ has to have both systems able to drive the wheels). And because the ICE is only running a generator, it can always run at the most efficient speed, which saves an enormous amount of fuel to begin with. Overall, you get the benefits of an electric vehicle – no fossil fuels are used as long as you don’t exceed the electric-only range; and it’s quiet, powerful and extremely efficent – without the range anxiety. And when you are driving on the ICE, you get superb fuel efficiency.

There are not very many of these kinds of vehicles around in the UK. Discounting the new Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV version and the BMW i3, both of which are well outside our price range, you’re left with two: the Chevrolet Volt and the Vauxhall Ampera. Chevrolet and Vauxhall are, of course, both General Motors, and these are basically the same vehicle, the Volt being the original, released in MY 2011. The Ampera is the Europeanised version of the Volt. GM don’t use the term ‘hybrid’ for the vehicle: they prefer E‑REV, or ‘Extended Range Electric Vehicle’.

Chevy is being wound down in the UK. And while Volts have been very successful in the US (and remain so – a new version comes out next year), neither variant did tremendously well in Europe, despite the Ampera winning a bunch of awards including Car of the Year in 2012, the year it came out here: there are about 6,000 on the road. It seems likely that this is because they were rather expensive when new – up in the fairly-large-BMW bracket while being a mid-sized reasonably luxurious hatchback. So I was expecting this to be out of range too… but not so! Although they have held their value pretty well, I was able to find a couple of 2012 Amperas – one not too far away – that we could actually afford. And following a test drive, we went for it. Previously owned by the dealership owner’s wife, it has been very well looked after; and it’s a very cool-looking Summit White.

I studied the forums and other information sources thoroughly before purchase, and as far as I could discover, it is one of the most reliable vehicles GM has ever produced: a known small risk of battery fire was fixed before the vehicles were even made for Europe; and while there is a known issue with a rather important bearing, only about 1–2% of vehicles have it fail and the problem and its solution are well-documented. According to a cleantech-oriented friend in the US, the Volt owners she knows are very pleased with their purchase.

The vehicle is extremely pleasant to drive, smooth and quiet, and even when the petrol engine finally kicks in, it’s still smooth and quiet and the performance (which includes its rather impressive acceleration) virtually unimpaired. The literature quotes the pure-electric range as “25–50 miles” – and that’s exactly what you get, depending on driving style and whether you have the heating on or not. On my first drive I got 48.8 miles out of the battery. The next day, leaving early on a cold morning, it went down to a mere 36 (tip: ‘pre-condition’ the driving compartment before leaving, while it’s still plugged in, which you can set it to do automatically).

The vehicle is extremely pleasant to drive, smooth and quiet, and even when the petrol engine finally kicks in, it’s still smooth and quiet and the performance (which includes its rather impressive acceleration) virtually unimpaired. The literature quotes the pure-electric range as “25–50 miles” – and that’s exactly what you get, depending on driving style and whether you have the heating on or not. On my first drive I got 48.8 miles out of the battery. The next day, leaving early on a cold morning, it went down to a mere 36 (tip: ‘pre-condition’ the driving compartment before leaving, while it’s still plugged in, which you can set it to do automatically).

The vehicle keeps a record of lifetime fuel efficiency. When I bought it, it was 110mpg (with 35,000 miles on the clock). I now have it up to 111. And indeed, as I expected, trips around Cambridgeshire can be made entirely on battery power – and if I can charge the car while the solar panels are outputting significantly more than we’re using, that operation is essentially free. Even on my weekly 200-mile round trip I managed over 90 mpg, thanks to being able to charge the car at my destination (where the Director of Marketing has a Tesla and is happy to share his charger) as well as at home. This knocks spots off a conventional Hybrid Synergy system. The car is learning what mileage I get from the batteries. When I first charged it, it estimated my battery range as 26 miles. It now thinks I’ll get 46. And that’s pretty much what I get.

It made sense to have a car charger fitted to the wall next to the driveway, rather than stick a cable out of the window, and there is a Government OLEV subsidy scheme that pays for a good chunk of the installation of a charger. I got mine (left) from ChargeMaster PLC in Luton, who were great to deal with – and having proposed a date, they actually came a couple of weeks early thanks to a cancellation. Charging the car from flat using the supplied EVSE (Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment), which plugs into a standard domestic socket, takes about 6 hours at around 11A charging current. However if you have a charger installed, you can charge in about 4 hours at 16A.

It made sense to have a car charger fitted to the wall next to the driveway, rather than stick a cable out of the window, and there is a Government OLEV subsidy scheme that pays for a good chunk of the installation of a charger. I got mine (left) from ChargeMaster PLC in Luton, who were great to deal with – and having proposed a date, they actually came a couple of weeks early thanks to a cancellation. Charging the car from flat using the supplied EVSE (Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment), which plugs into a standard domestic socket, takes about 6 hours at around 11A charging current. However if you have a charger installed, you can charge in about 4 hours at 16A.

The Volt/Ampera has what is called a Type 1 (or J1772) connector (right), a fairly compact latching plug that goes into the left front of the vehicle.

The Volt/Ampera has what is called a Type 1 (or J1772) connector (right), a fairly compact latching plug that goes into the left front of the vehicle.  However most of the chargers you find in the wild in Europe are equipped with what are called Type 2, or Mennekes connectors (left). It made sense, therefore, to get a cable from one to the other so I can charge the vehicle at a public charging point at the destination (there is rather less point charging ‘on the road’ as the charging rate is only about 16 miles an hour, and that’s what the ICE is for!). Having this cable in the back of the car, it made sense to have a Type 2 socket on the home charger instead of the more usual tethered Type 1; and while I was at it, I future-proofed myself by getting a 30A charger in case friends with a Tesla call round or we upgrade down the line.

However most of the chargers you find in the wild in Europe are equipped with what are called Type 2, or Mennekes connectors (left). It made sense, therefore, to get a cable from one to the other so I can charge the vehicle at a public charging point at the destination (there is rather less point charging ‘on the road’ as the charging rate is only about 16 miles an hour, and that’s what the ICE is for!). Having this cable in the back of the car, it made sense to have a Type 2 socket on the home charger instead of the more usual tethered Type 1; and while I was at it, I future-proofed myself by getting a 30A charger in case friends with a Tesla call round or we upgrade down the line.

I would note when it comes to public charging sites, although there are quite a lot of them (more all the time, and many will take a Type 2 plug), they all belong to different networks that generally don’t have exchange agreements. As a result you may find you need a pack of RFID cards from the common networks and wave the right one over the charger to unlock it. In fact 85% of charging is carried out at home, and as I note, I won’t normally be plugging-in at motorway services, but I still want to be able to use a public charger at the end of a long journey, so having those cards (several of which are free) is probably worth doing.

(Main photo: General Motors/Vauxhall)

April 26, 2015 Comments Off on An Electric Car (at least part of the time…)

Solar panels — a year on

We wanted to install solar panels for years — in my case decades, since I was involved in the “Alternative Technology” magazine Undercurrents in the 1970s. In the past, the idea of a solar PV system has just been too expensive (friends down the street paid £15,000 for their system just a few years ago), but we’d been watching prices fall until, by the middle of 2014, it looked as if prices had fallen to an affordable level.

We interviewed four companies and it quickly became evident that the height of the roof wouldn’t allow the conventional 16 panels in two rows “portrait” style that is common for a 4kWp system – they would have to be mounted too close to the top and bottom of the roof (you need 500mm clearance all round — otherwise you can risk less stability in high winds). We could, however, manage two rows of six, “landscape” style. The companies we talked to varied in the amount of work they did specifying the installation, and I regard actually getting up into the loft and taking real measurements as an indicator that the installer is worth considering.