Category — Audio Production

More Gryphon Restoration

As I noted previously, there are some technical challenges associated with recovering the recordings of the band Gryphon that I made in July 1974 during their landmark performance at the Old Vic.

A notable problem was the fact that there was a bass DI in the main PA mix (which was the basis for the recording, with the addition of a coincident pair of ambient mics) and this was often extremely loud in the balance — sometimes enough to cause intermodulation distortion with the rest of the mix (it’s possible that this was overloaded on the recording).

To give you an insight into the results of this factor, here’s another piece from the Old Vic tapes. This is Opening Number, the band’s, er, opening number. Note the effect of the bass entry about half-way through.

This is an example of why it may not be possible to get an album’s worth of tunes out of this recording. However it will be worth our trying to recover the stereo master tapes to see if the distortion is on there too (these transfers are from a copy).

August 21, 2018 Comments Off on More Gryphon Restoration

Restoring an Ancient Gryphon

This month has seen the release of the new album by old friends of mine, Gryphon. The album, ReInvention, is their first for 41 years: the band, re-formed and augmented, though now without the presence of co-founder Richard Harvey, is poised, at the time of writing, to perform the new album in the Union Chapel.

In honour of the new release I thought it might be interesting to attempt to resurrect what is the first recording I ever made of the band (I was their sound engineer in the studio and on the road from 1974–5, culminating in the recording of the Raindance album across Midsummer 1975, which I engineered and co-produced). This was a recording of the live performance given at the Old Vic on 14 July 1974 – the first and, I believe the only, rock concert ever to have been held at the Old Vic or hosted by the National Theatre. Gryphon had recently been commissioned to write the music for Peter Hall’s National Theatre production of The Tempest, which had premiered on March 5, and had recorded their second album, Midnight Mushrumps (a reference to Prospero’s speech, 5.1.39) including a suite based on the music for the play, with Dave Grinsted at Chipping Norton Studios in the Cotswolds.

The Old Vic performance was right at the start of my involvement with the band and I was yet to be responsible for their sound live or in the studio. However for the occasion of the Old Vic performance I was able to obtain a Teac 3340 4‑track recorder and situated it beside the mixing desk on the balcony. I had a pair of AKG D‑202s, excellent all-round dynamic mics, arranged in a coincident pair as close to the centre of the balcony as I could get, and recorded these on one pair of tracks on the Teac; and in addition I put a stereo feed from the board on the other two tracks. The resulting 4‑track tape gave me a clean feed of the PA mix, with the addition of audience reaction and ambience from the room mics – particularly effective on the percussion. However as we were on the balcony there was a delay between the PA feed and the room mics, so when I mixed-down the 4‑track to stereo I put a delay on the PA feed tracks to bring them into sync with the room mics. This also gave me the opportunity for a little fun, as I could vary the delay slightly to give a slight flanging effect on tracks like Estampie, which Richard Harvey refers to in the intro as “a mediæval one-bar blues”, an effect which had been used on the original album recording for a similar purpose.

The disadvantage of the PA feed was that it included a bass DI run at considerable level, and as a result, Philip Nestor’s bass-playing features prominently in the feed. So much so, in fact, that the bass causes some intermodulation distortion with other instruments, rendering some of the pieces sadly virtually unusable. However with some judicious use of EQ around the 80–200Hz mark the bass can be quietened-down enough for a reasonable balance to be achieved in many cases.

Sadly the original 15in/s mixdown master of this recording is lost, and believed to be in Los Angeles. However I made a cassette copy of the three reels which I hung on to. They were BASF Chrome cassettes and I recorded them with a Dolby B characteristic on a machine that I had evidently been able to set the Dolby level on correctly as the results are quite respectable. For these experiments I transcribed the cassettes from a Technics M260 kindly provided by Duncan Goddard, who is a highly talented restorer of vintage analogue recorders, having previously supplied my trusty ReVox PR99 and A77.

I digitised the audio via a Focusrite Scarlett interface and brought it into Adobe Audition, my DAW of choice for stereo audio production. I cleaned up the noise floor with Audition’s built-in noise reduction tools and a couple of Wave Arts restoration plug-ins, using the Audition parametric EQ to restrain the bass end. Here’s an example of the results: the mix of Estampie referred to above. And I hope you like it.

August 20, 2018 Comments Off on Restoring an Ancient Gryphon

Inside a Telefunken S600 Belt-Drive Turntable

I hadn’t intended to end up with more than one turntable, but I now have no less than four, all of which work. The most recent one I’ve been working on is a Telefunken S600, which turns out to be an exceptionally well-designed turntable with a number of ingenious bells and whistles.

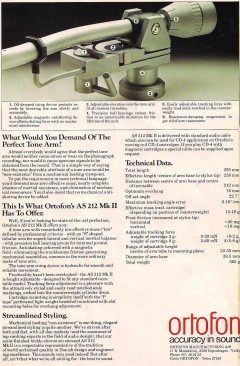

As I detailed previously, I wanted to replace the standard tone arm on a Lenco L75 turntable with an Ortofon AS-212. These are found (amongst other places) on Telefunken S600 belt-drive turntables, so I sourced one from Germany to steal the arm — but fellow members of internet groups I belonged to were horrified that I would do this to an actually rather nice turntable. So I relented, and one of my correspondents found a New Old Stock AS-212 that I duly installed on the Lenco.

Meanwhile, the S600 arrived from Germany, in rather a sorry state. Despite being very well packed, the plastic cover was cracked almost in two and the back of the arm had gone missing along with the counterweight. The well-known international shipping company had both damaged it and mis-delivered it: the incorrect recipient had opened it and lost some of the bits. So when it got here I wouldn’t have been able to pinch the arm for the Lenco anyway.

But now I had learned that these decks were actually quite good, I decided to attempt to repair it. And if it was actually a good deck, I might want to use it as my main deck — in which case it needed a modification to run at 78rpm.

Fixing the arm

The big problem was the arm itself. This consists of an S‑shaped arm tube with a bearing housing on the end made of some mysterious hard rubbery material. A small tube containing two sets of four 1.2mm ball bearings goes transversely through the housing and is held in place by two pointed set-screws that have to be set up exactly right so that the arm sits centrally in its holder with freedom to move up and down but with no play. The housing has an extension stub on the back, and on to this mounts a threaded tube on to which the counterweight screws. In this case, the stub had snapped off the back of the bearing housing and with it had gone the threaded tube and counterweight.

There were several possible solutions. Replacement bearing housings are available on eBay from time to time, made either of Delrin or brass. The threaded tube is available too. I could replace the bearing housing (get the housing off the arm tube, push the bearing tube through and put it into the new one, add the threaded tube and reattach the arm). I could consider getting a threaded tube and fitting something inside it that I could push into the back of the bearing housing and glue it in place. I got the bits to do the latter, namely the threaded tube and some metal-filled resin. But the procedure seemed a bit dodgy, frankly. Would it stay stuck? Would the resin go where it shouldn’t? Would it look decent? I looked for a new bearing housing instead, but found only brass ones, which seemed like overkill to me — the black Delrin ones didn’t seem to to be available at the time. But then a contact of mine kindly came up with a solution: a complete replacement arm with the arm tube, bearing housing (with bearings) and threaded tube — plus an original counterweight. Excellent. All I had to do was to fit the arm — and send the old one back to him.

The replacement arm assembly duly arrived, and is shown here. The supplier very kindly taped up the bearing housing so the balls couldn’t fall out (I had obtained some spares in case they did, but I didn’t need them). First I needed to de-solder the arm leads, which meant getting the turntable out of its plinth.

This simply required undoing three screws. Telefunken really designed these turntables thoughtfully. You lift up the turntable, turn it vertically and then you can slide it into grooves in the plinth where it stands safely so you can work on it.

Here’s the innards of the turntable, and there are a lot of things to talk about here in due course. Click on the image to see it up close. I de-soldered the arm wires (they attach to a terminal strip bottom right next to the muting relay) and then put the deck back in the plinth. I had armed myself with a pair of tiny circlip pliers with 1mm prongs to fit the lock-nuts surrounding the bearing set-screws (one set of both on either side — you can see them in the broken original arm image above) and now attempted to loosen them. Pleasingly they loosened surprisingly easily and I was then able to unscrew the set-screws enough to carefully lift the arm out. Thankfully the little ball bearings stayed in there too. So I taped it up ready to send off. The new arm went in with surprisingly little trouble too. First I led the wires through the arm column by putting them into a drinking straw and pushing that down the hole in the centre of the column. Then, using a business card as a feeler gauge to centre the arm in the mounting, I held the arm in place and gently tightened the screws. Then holding the screw in position with a screwdriver I tightened the locknut, first on one side, then the other. It took about three goes to centre the arm successfully and lock the screws in place, but the result was an arm that exhibited negligible resistance when moving in its bearings. Exactly what was required. This pic shows the new arm in place minus the counterweight.

Here’s the innards of the turntable, and there are a lot of things to talk about here in due course. Click on the image to see it up close. I de-soldered the arm wires (they attach to a terminal strip bottom right next to the muting relay) and then put the deck back in the plinth. I had armed myself with a pair of tiny circlip pliers with 1mm prongs to fit the lock-nuts surrounding the bearing set-screws (one set of both on either side — you can see them in the broken original arm image above) and now attempted to loosen them. Pleasingly they loosened surprisingly easily and I was then able to unscrew the set-screws enough to carefully lift the arm out. Thankfully the little ball bearings stayed in there too. So I taped it up ready to send off. The new arm went in with surprisingly little trouble too. First I led the wires through the arm column by putting them into a drinking straw and pushing that down the hole in the centre of the column. Then, using a business card as a feeler gauge to centre the arm in the mounting, I held the arm in place and gently tightened the screws. Then holding the screw in position with a screwdriver I tightened the locknut, first on one side, then the other. It took about three goes to centre the arm successfully and lock the screws in place, but the result was an arm that exhibited negligible resistance when moving in its bearings. Exactly what was required. This pic shows the new arm in place minus the counterweight.

The turntable was now back more or less to its original specification, give or take. I ran it up and found that it reached 33 or 45 very quickly considering the weight of the beautifully-balanced platter, and the speeds were rock solid. The touch buttons for speed and stop all worked as intended and the speed control trimmer knobs worked well. I hadn’t even had to replace the electrolytic capacitors. (If I had needed to, the information required – along with lots more about these turntables – is here.)

The turntable was now back more or less to its original specification, give or take. I ran it up and found that it reached 33 or 45 very quickly considering the weight of the beautifully-balanced platter, and the speeds were rock solid. The touch buttons for speed and stop all worked as intended and the speed control trimmer knobs worked well. I hadn’t even had to replace the electrolytic capacitors. (If I had needed to, the information required – along with lots more about these turntables – is here.)

Bells and whistles

This turntable has several bells and whistles. The main ones are to do with the arm lift. This can be actuated manually with the lever — there is a Bowden-style cable from the lifter lever to a fluid-damped dashpot under the arm rest. There is a locking arrangement that only lets the lever lock in the down position if the turntable is under power, and if you hit Stop it lifts up the arm (and when the arm is lifted, incidentally, the relay mentioned earlier mutes the audio).

It is also intended to lift the arm at the end of a side. This is accomplished in a rather ingenious way. Look at the photo of the underside above and you’ll see that there is a slotted copper arc just to the left of the motor control board. This is attached to a very lightweight arm that is linked to the tonearm, and swings across under the turntable as the arm tracks a disc. Just next to the copper arc (which we’ll come to in a moment) is a V‑shaped cutout. This is the clever bit. When the arm reaches the end of a side, that V passes between a big frosted bulb (just below the centre of the image) and a light-dependent resistor, shading it from the light. (Why the V I don’t know: it will mean that the illumination drops slowly rather than at once. Why?) This is detected and hits Stop on the turntable, which also powers-down a solenoid to release the arm-lifter to lift the arm. That is what is supposed to happen, but unfortunately it didn’t work. In fact it is a little surprising that the turntable would run without holding a button down. The bulb had expired.  It looks very much like a W5W auto bulb but it’s only supposed to take 100mA. Luckily there are W5W replacement LED bulbs that run that kind of current so I popped one in. On power-up this duly illuminated, and now the arm lifted and the turntable stopped somewhat before the arm reached the end of its travel, corresponding to just before the locked groove on a disc.

It looks very much like a W5W auto bulb but it’s only supposed to take 100mA. Luckily there are W5W replacement LED bulbs that run that kind of current so I popped one in. On power-up this duly illuminated, and now the arm lifted and the turntable stopped somewhat before the arm reached the end of its travel, corresponding to just before the locked groove on a disc.

While we are looking under the turntable, let’s look at what that copper arc does. As the arm swings, it stops the light from another, smaller bulb, directly to the right of the main bearing, from falling on the end of a light-pipe — that little clear tube going up to the top of the deck and past the orange string (which is the interlock between the power switch and the arm lifter). It ends in a little bezel on top of the deck. The light is thus visible from above the deck except when it’s obscured by that copper arc — which means the light is visible when the arm is beyond the platter and when the light can shine through the three slots in the arc, which correspond to the edges of a 7in, 10in and 12in disc. So basically it tells you where to put the arm for the start of a disc.

I thought the drive belt a little stretched and worn so obtained a replacement from thakker.eu (for the S500, a simpler version of this turntable, but with the same motor/subplatter arrangement).

A speed mod

With the deck returned to its original specification, next came the modification I wanted to perform — to get it to run at 78rpm as well as 33 and 45. I had asked about this in the Vinyl Engine online forum and a gentleman had kindly looked at the circuit diagrams I had found and suggested how to do it. It turns out that this design of turntable was actually licensed from Philips, though Telefunken made some extensive subsequent modifications. It’s a DC servo-controlled motor arrangement, and in some of the original Philips models using the same motor and control board design, the turntable can actually do 78 rpm right out of the box — so there was no reason why this shouldn’t work.

The answer, my respondent suggested, was to put a resistor across the main 45rpm speed control resistor (R133) to reduce its value, then use the 45rpm speed knob to fine-tune the speed to 78. I decided to go a little beyond that and put a trimpot in series with the fixed resistor so that I could set the speed to 78 with the 45rpm speed control knob in the centre position as it was for 45, and not have to adjust anything unless I wanted to run at a special speed like 80rpm for example. It took some experimentation to get the values right: eventually I used a 47k? fixed resistor in series with a 10k? trimmer. I soldered these to a miniature DPDT toggle switch that I mounted in the lower right-hand side of the plinth, with a hole to access the trimmer, and a LED and series resistor, powered from the lamp supply, on the other poles of the switch so a red light comes up when you select 78. And it works beautifully — here’s a Conroy music library 10in 78 spinning at the right speed!

Finally, I replaced the audio output cable, adding a pair of Neutrik phonos in place of the original 5‑pin DIN, and ran a chassis ground wire along the audio cable with a spade connector on the end. In fact this is of limited use as the mains on the turntable goes via a double-pole switch straight into a double-wound transformer: the chassis and all the audio grounds are connected together and have no connection to the mains side. Untangling this to provide separate audio and chassis ground turned out to be a real pain — to retain the muting relay function would have required serious rewiring — so I left well alone, and in fact it works fine, and the chassis can be connected to mains earth if desired.

The turntable has a cast stroboscope at the edge with its own neon lamp, but of course it doesn’t include 78, so I printed out an image of an old Garrard strobe for now and that works fine — maybe I’ll pick up one of the Lenco metal ones at some point.

In operation

So, now to try the turntable out. I mounted the Shure M97xE in a skeleton headshell originally acquired for my TT-100 and set it up for 16mm overhang (tricky as you can’t move the arm to the centre spindle: I cut a piece of wire to length as a measure) and lined it up with a cartridge protractor: it lined up perfectly. Setting the tracking weight and anti-skate accordingly, I played a tone disc with the arm at different positions and the waveform and sound were clear and undistorted throughout. I then played some music, and found this under-recognised turntable, believed by many to out-perform many other belt-drive turntables of the period such as those by Thorens, was a marvellous performer, delivering an excellent, open and stable sound just as I would like it.

So, now to try the turntable out. I mounted the Shure M97xE in a skeleton headshell originally acquired for my TT-100 and set it up for 16mm overhang (tricky as you can’t move the arm to the centre spindle: I cut a piece of wire to length as a measure) and lined it up with a cartridge protractor: it lined up perfectly. Setting the tracking weight and anti-skate accordingly, I played a tone disc with the arm at different positions and the waveform and sound were clear and undistorted throughout. I then played some music, and found this under-recognised turntable, believed by many to out-perform many other belt-drive turntables of the period such as those by Thorens, was a marvellous performer, delivering an excellent, open and stable sound just as I would like it.

The only problem I have now is what to do with all these turntables. I really don’t want to get rid of either the Lenco or the Telefunken and I think the former will end up on the main system downstairs while the Tele stays in my studio for transcription (alongside the excellent Technics SL‑7 linear tracker, which doesn’t do 78).

November 3, 2016 Comments Off on Inside a Telefunken S600 Belt-Drive Turntable

Modifying an Idler Turntable

One of my activities is transferring archive music library master tapes to digital, so they can be made more widely available again. This is not always straightforward, and it’s sometimes necessary to transfer excerpts from disc if the master tape is damaged in some way. To do this requires a decent vinyl playback system. This article is about how I put one together.

Sometimes there are problems with the old tapes — such as oxide or backing shedding, and in particular when the backing binder becomes sticky and stops the tape passing through the machine. Another issue is the adhesive used in splicing tape becoming sticky (although it is specifically supposed not to) and this can result in oxide fragments being pulled off the front of a track resulting in dropouts. And unlike the solutions for sticky binder and shedding (such as baking the tape or running it through a white spirit or isopropyl alcohol-soaked pad) sticky splicing tape causing damage is difficult to avoid, even if winding very carefully.

On more than one occasion, problems like this, or major dropouts, tape damage and other issues, mean that a (usually short) section of the master tape is unrecoverable. The solution, then, is to try and find a copy of the library disc pressed from the master, capture the appropriate section, match it in level and other characteristics and then edit it into the version transferred from tape.

A better vinyl playback system

To do this effectively requires a decent record deck, and while the unit I’ve had for some time — a Numark TT-100, essentially a DJ turntable — does a good workmanlike job, and has the benefit of 78rpm (which is sometimes necessary) as well as 33 1/3 and 45, I though it worth spending a bit of time and money acquiring a superior vinyl playback system.

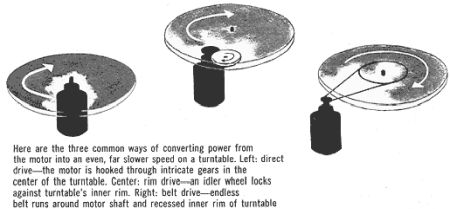

There are basically three types of ways in which the motor can drive the platter in a turntable: Idler Drive, Belt Drive and Direct Drive. They’re illustrated in the diagram above. It should be noted that there is often more than one way of implementing all three of these methods: Direct Drive — often found in DJ turntables — can involve the actual platter being part of the motor, rather than requiring the “intricate gears” suggested above; with Belt Drive the belt may go round the entire platter and not a sub-platter; and in the case of idler drive the idler may be horizontal (as shown — Garrard used this) or vertical (as in the Lenco designs).

The Lenco L75

I decided on an idler design as these are highly-regarded for their sound quality. While it would have been nice to have, say, a Garrard 401 transcription turntable, this was well out of my price range and I settled instead for a Swiss-made Lenco L75. I found one for a good price and a relatively short drive to Norwich. I have never actually owned one of these before, though I remember one from the school music room, many years ago (they were common in educational institutions).

As soon as I got it home I reviewed it visually, and all looked good, so I powered it up and it ran fine, solidly at each speed. It had a rather cheap and nasty original plinth that (still) needs to be replaced with a proper, solid one. These decks perform best without the benefit of the springs provided supporting it in the plinth, so I removed them.

Updates: V‑blocks and wiring

Then I looked at the so-called “V‑blocks” in the arm suspension. NOTE that I didn’t use the original Lenco arm in the end, but this info may be helpful if you are. The arm has a knife-edge bearing that allows it to swing up and down. The knife edge, attached to the arm tube, rests in two V‑shaped blocks, one either side, and they are notorious for degrading. Sure enough, mine had decayed into solid lumps that looked like yellowed teeth. I carefully scraped them out, cleared the holes, and replaced them with a pair of “desmo” V‑blocks sourced from eBay. The whole operation was remarkably straightforward.

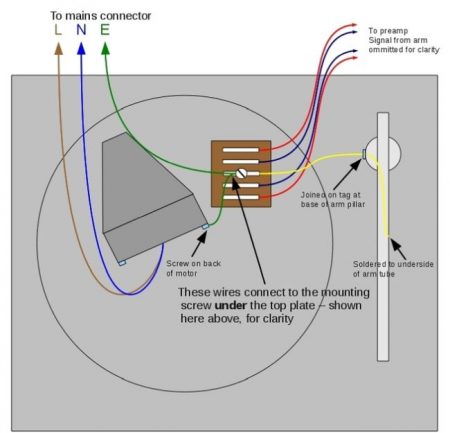

Next I reviewed the wiring. The audio cabling centres around a terminal block on the underside of the deck plate and here the wires from the tonearm headshell meet the shielded cables going to the outside world. The left and right signals and their respective ground leads need to by electrically separate from the chassis ground (a yellow wire also leading out of the plinth): in my case they were, but I replaced the coax with modern cable and the DIN plug on the end with two gold-plated phonos. The metal body of the arm is grounded to the chassis.

On the mains side, the circuit is simple: Live and Neutral come in, one leg goes via a switch to one side of the motor and the other side goes to the motor. This might have been fine 40 years ago but today, with old electrical systems, we probably want a better approach. The suggestion in the Lenco Heaven forum — where all the experts on the subject of these turntables hang out — is to follow the wiring shown below, drawn by Stephen Clifford:

Not shown above is the fact that the yellow (chassis ground) lead is extended out of the plinth to be connected to the appropriate connector on a phono preamp if required.

Impossible hum

Having carried out all the re-wiring, I installed a cartridge and ran it up. And it hummed, badly. Now you do not need the yellow lead connected to ground on the phono preamp and the ground connected in the mains plug as it will cause a hum loop, but in this case I could not get the hum to go away, whatever I did. I tried cleaning the headshell and arm contacts, different earthing schemes, different cartridges and even different preamps, but to no avail.

It seemed likely to me that the problem lay in the wiring to the headshell connector but this seemed fairly hard to address. In addition (and no doubt purists will hate me for saying so), I found the original arm rather clunky. So, even though I had carried out the task of replacing the V‑blocks et al, I decided to replace the tone arm.

The Ortofon AS-212 as a replacement arm

There are only a couple of tone arms that will slot more or less straight into a Lenco, ie they are the right length etc to fit. The one that appealed to me was an arm made by Danish manufacturer Ortofon (famed for their pickup cartridges) the AS-212. But where to find one? Hunting around netted me a gentleman in Germany selling a Telefunken S600 deck — these were fitted with this arm — at a good price.

There are only a couple of tone arms that will slot more or less straight into a Lenco, ie they are the right length etc to fit. The one that appealed to me was an arm made by Danish manufacturer Ortofon (famed for their pickup cartridges) the AS-212. But where to find one? Hunting around netted me a gentleman in Germany selling a Telefunken S600 deck — these were fitted with this arm — at a good price.

Sadly, when it arrived, the rear of the arm had disappeared and the lid of the turntable was cracked — a result of the shipping company mis-delivering it and the erroneous recipients opening it.

Not only that, when I mentioned my intentions on a Facebook group I belong to specialising in vintage equipment, they were horrified. The Telefunken S600 was an excellent belt-drive deck, they said, probably out-performing the Thorens decks of the time, and should not be vandalised and left ‘armless’. So I decided to repair it, and see if I could find a spare AS-212 arm for the Lenco, then keep the one I preferred and sell the other. The Telefunken story is for another article.

Immediately up came an offer on the Vinyl Engine forum of a complete AS-212 arm, boxed: a replacement arm for a Telefunken. At the same time I received an offer of a replacement armtube, bearing and counterweight. I could use the former on the Lenco and the latter to repair the Telefunken.

Preparing the arm for fitting

The new-old-stock complete AS-212 assembly duly arrived, and I acquired a mounting base for the new arm to fit the Lenco deckplate hole — the Ortofon is a different diameter and thus needs a different fitting. These are available on eBay: I bought a silver-coloured one.

Before fitting to the Lenco, the new arm needed some dismantling. I decided to use the Lenco arm lifter — pretty much obligatory, in fact, with an AS-212 designed for an S600, as the Ortofon arm comes with an oil-damped lifting cylinder with just a bottom pin that is supposed to fit into the S600 lifter mechanism, a clever Bowden-style cable arrangement: thus it does not include a complete lifter system. So I removed the lifter cylinder and arm rest, leaving a 10mm hole in the body of the arm, which I decided to fill with a suitably-sized circular bubble spirit-level, secured with the existing set-screw. Adjacent to it in this picture is the AS-212’s natty no-contact magnetic anti-skate system. The little hole formerly took a pin on the lifter to stop it rotating. I found a use for it later.

I also removed the arm clip from the AS-212 (the rod to the left of the above image is the back of it) so as to use the Lenco one, which is the correct diameter to hold the arm securely.

Next step was to mount the arm column in the new base. This was easily done. I set the height up by attaching a cartridge and adjusting the height so that the arm was horizontal with the stylus resting on a disc. I lined up the body of the arm to be parallel to the edge of the deck-plate and it looked great. I tightened the set-screw and there it was.

A few modifications

An initial problem was that the arm wiring was not as long as the original Lenco, so I moved the audio connection tag strip to somewhere nearer to the arm so it reached, and under the deck plate instead of on top.

This picture also shows the revised power wiring mentioned earlier. I made a new hole in the plinth for the audio cables to exit so that they didn’t run parallel to the power cable.

The Lenco lifter actuator lever is quite long, and actually fouled the arm when at rest, so I shortened it. Actually, I was going to bend it outwards but the top bit snapped off. Ooops. It’s still easy to reach and use: a short piece of black heatshrink tubing and it looks the same as the original, but shorter.

The biggest challenge was getting the lifter to work. The Lenco lifter arm is quite deep, and when lowered rested on the top of the Ortofon platform long before the stylus was able to reach the record. I thought this could be solved simply by shortening the lifter arm to avoid the edge of the platform, but this was a Bad Idea as the arm could drop down and hit the deck plate between rest and the start of a disc, and tended to fall off the end of the lifter. The solution instead was to file the underside of the end of the lifter arm where it overhung the platform to about half its depth. This allowed the lifter to drop far enough to allow the stylus to reach the record. All the elements of the arm are able to be adjusted for height: the lifter arm, the arm rest, and of course the arm column.

It’s worth noting that there is a small caveat here. The Lenco arm rest, which I’m using, allows the arm to be unclipped by moving it vertically. It is possible, once unclipped, for the arm to swing outward, whereupon it will fall off the lifter arm and could drop down and clout the cartridge on the power switch or the deck plate itself. I made this impossible by inserting a thin rod into a hole left by part of the original AS-212 lifter mechanism and bending it over and above the arm to stop this from happening. You can see the hole in the close-up of the bubble level a couple of images up. While I was at it, I added a cut-down self-adhesive foot to the right-hand front of the platform so that the arm couldn’t drop if it went backwards. Another approach would have been to reinstall the Ortofon arm clip, which opens towards the turntable and is thus less likely to allow the arm to go backwards. However this would require removing the Lenco arm-rest, leaving a hole in the deck plate.

Next I needed to mount the cartridge more accurately. The AS-212 needs a 16mm overhang — ie if you swing the arm across to be over the central spindle, the stylus should be 16mm to the left of its centre. This proved to be quite difficult to do: the slots in the headshell only just allowed it with the cartridge as far back as it would go. But it worked, and I was also able to set up the null points successfully with a protractor, with the cartridge parallel to the groove at both points. The correct way of fitting the cartridge is to use the two threaded rods on the underside of the manual lifter prong, but in my case, although I have several Ortofon headshells, none of them would actually hold the Shure M97xE, either because they were too long, too short or there wasn’t room for the nuts. So I mounted the cartridge with a pair of bolts and fitted the manual lifter separately (see below).

Playing some records

With that done, I carried out a final check of the settings, including: checking that the arm really was horizontal while playing and thus the Stylus Rake Angle was correct (I think this is a better way of looking at it than by addressing the Vertical Tracking Angle, and I don’t have a microscope); setting up the tracking weight for my Shure M97xE; and adjusting the AS-212’s elegant magnetic anti-skating setting.

With that done, I carried out a final check of the settings, including: checking that the arm really was horizontal while playing and thus the Stylus Rake Angle was correct (I think this is a better way of looking at it than by addressing the Vertical Tracking Angle, and I don’t have a microscope); setting up the tracking weight for my Shure M97xE; and adjusting the AS-212’s elegant magnetic anti-skating setting.

And then I played a record for the first time — but not a terribly exciting one. It was the B‑side of a KPM Music Library test pressing of pieces by Richard Harvey, consisting solely of a 1kHz tone. I was able to listen to the tone quality at various points across the disc and was very pleased with how pure the tone was at all points.

Then to play some actual music: the content side of the same disc. I was immediately very impressed with the wide frequency range apparent on playback, and a good tight feeling to the bass end. The overall sound was very clear, clean and detailed, and the stereo imaging nice and stable. Excellent.

My view is that this is an exceptional combination of arm and deck and I am very pleased with the results so far, though I need to give it a lot more critical listens. But in theory, all that’s needed now is a new plinth that does the deck justice.

I have, incidentally, kept all the Lenco bits I’ve removed, included spares of items I modified (eg the lifter actuator lever and the lifter arm) so that if it ever needs to be restored to its original spec, this can be done.

October 11, 2016 Comments Off on Modifying an Idler Turntable

Poetry at Relay for Life

I love Shakespeare, but I’ve never really thought of performing any.

However when we were preparing for the Relay For Life of Second Life Telethon, several members of the team were invited to record a series of poems to be played during the Luminaria ceremony (one of the most moving parts of the event).

The Luminaria Ceremony occurs at every Relay For Life event, whether in the organic world, or as in our case, in a virtual world. As the sun sets, luminaria lining the track light up the night. A hush falls over the crowd that had been overflowing with celebration. Participants, survivors, and caregivers then gather to remember loved ones lost to cancer and to honour those whose fight continues. The ceremony in Second Life included a wonderful additional feature: the releasing of illuminated Chinese lanterns into the night sky (see Beq’s picture above, taken in front of her amazing Escher build that you can just make out).

The official commentary is carried by T1 Radio, and they read a list of names, between which they play pieces of music. Now, they have a licence to play commercial records, but we don’t, so this year they kindly gave us a running order and timings and we were able to determine what was to go in the slots occupied by music in their coverage, so we could “opt out” to our own audio programming. This was the purpose of the pre-recorded poems. Members of our team put these recordings together with production music (mainly by Kevin MacLeod, see credit below) to create a series of really beautiful sequences, which I will hopefully be able to link to for you shortly where they’ll have full credits — they’re being assembled into a series of short videos accompanied by images of this year’s campsites.

One of the two pieces I chose to record was this speech from Prospero in The Tempest:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve;

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. (IV.i.148–158)

In addition to sending the voice-only recording off to the guys for incorporating in the sequence, I found a piece of music [Virtutes Instrumenti, Composed and performed by Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/

August 1, 2013 Comments Off on Poetry at Relay for Life

What is authenticity?

My attention was drawn to a rather interesting article in the Washington Post late last year on the use of “historical” FX in the movie “Lincoln”. Spielberg actually tried very hard to capture “authentic” sound effects — Lincoln’s actual pocket watch ticking, the ring of the bell of the church he attended, and so on.

Quite a lot of the time, in my experience, recording actual sounds doesn’t give you as effective a result as faking it with something else, but with sounds like those mentioned in the article, you can see why it might be worth chasing the originals. Apart from the fact that people notice when details are wrong — the BBC used to get letters if they used the sound of the wrong vintage plane in a radio play, for example, and they probably still do — there’s an interesting philosophical dimension here, about what we mean by “authentic”.

In the days of phonographs and cylinders, it was common to make recordings of famous people making famous speeches and other spoken material. Very often these were not recorded by the actual person claimed. But the degree of “realism” — or may we say “authenticity” — was judged by how well the performer represented the original person, not by whether or not it was the original person making the recording.

Similarly, we can read reviews of Clément Ader’s historic stereo relays from the Paris Opera House to the World Expo in Paris in 1881 and be surprised that listeners found the experience of listening to a pair of early moving-coil telephone earpieces fed by carbon microphones down hundreds of metres of wire so realistic. Surely it was nothing like hi-fi as we know it.

Exactly what we mean by “authenticity” has certainly changed over the years. And there is a distinct difference between accuracy and experience. When I’m in the studio, I try to do my best to ensure that the listener at home or on the move hears as close as possible to what we heard in the control room when we played back the master mix and said “That’s the one”. Is this a reasonable thing to seek to achieve? Or should we be striving to give people the best experience, regardless of authenticity? I touched on this the other day referring to miming at the Presidential Inauguration: definitely a case of going for the best experience.

To me, you can apply the old slogan “The closest approach to the original sound” to any recording as long as you know what you mean by the “original sound”. In my opinion this is generally the master playback, not what it sounded like out in the studio. In the case of multitrack layered popular music this is obviously the case. But how about a recording of a string quartet? Are you trying to give people the audio experience they would hear in a concert hall (I say “the audio experience” because you would be missing all the non-audible cues), or are you trying to give them the experience you had when you signed off the master playback? Well, probably, the latter.

It would be worth pointing out that listening to concert-hall recordings is frequently not very much like being there, because you only hear the music. Even if you recorded the concert Ambisonically, captured the entire soundfield and played it back faultlessly, you would only have captured the audio of the event, not the experience. This being the case, what is often done is to make the recording more lively and exciting to make up for the non-audio aspects of the performance. Close mics, changes of dynamics, and other techniques do make the playback more involving. In my opinion there is nothing wrong with this as long as it’s not dishonestly presented. Once again, the original sound is what’s heard in the control-room, not in the concert-hall — and that’s what you should be wanting people to hear at home.

It’s all very well claiming to reference playback systems to the sound of actual musical instruments, but that begs all kinds of — generally unanswerable — questions about how you established the sound of the instruments in the first place. What was your reference? Where did you hear them? How far away were you? Who was playing what? What was heard in the studio on master playback, however, is a perfect reference: it’s what the production team thought was the best representation of every aspect of the music, the composer, the artist and the performance — and more. They regarded it as the best communication between all those factors and the person listening to the recording. And, in my opinion, it’s the only thing you can reasonably expect to try to recreate for the listener.

For a further consideration of the philosophical implications of “authenticity”, in the context of “Lincoln”, check out this blog post.

February 1, 2013 Comments Off on What is authenticity?

On Delia Derbyshire for Ada Lovelace Day

Today, March 24 2010, is Ada Lovelace Day, the day when we celebrate women in science and technology and their achievements – typically by blogging about them. You can find out more about Ada Lovelace Day at the Finding Ada web site, but here’s the basic gist:

Ada Lovelace Day was first celebrated in 2009, when over 2,000 people blogged about women in technology and science and the event receive wide media coverage. This year the hope is to get 3,072 people to do the same. Ada Lovelace Day is organised by Suw Charman-Anderson, who writes:

“Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace was born on 10th December 1815, the only child of Lord Byron and his wife, Annabella. Born Augusta Ada Byron, but now known simply as Ada Lovelace, she wrote the world’s first computer programmes for the Analytical Engine, a general-purpose machine that Charles Babbage had invented.”

And there’s plenty more where that came from.

The marvellous logo shown above was created by Sydney Padua and Lorin O’Brien and appears on the former’s wonderful 2D Goggles comic web site.

Delia Derbyshire

I’ve been interested in electronic music for decades, and I suppose one of my greatest influences was the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, sadly disbanded in March 1998 during the era of the BBC “internal market” under Director-General John Birt, when departments had to operate at a profit or close. This resulted in absurdities like it becoming cheaper to nip down the street from Broadcasting House to HMV in Oxford Street to buy a CD containing a piece of music to use in a programme rather than obtaining the track via the BBC Record Library.

Delia Derbyshire (1937–2001) was born in Coventry, my home town, and completed a degree in mathematics and music at Girton College Cambridge. In 1959, she famously applied to Decca to work at their recording studios in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead and was turned down, being told that they didn’t employ women.

After a stint with the UN in Geneva and with music publisher Boosey and Hawkes she joined the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in 1962, which, in those days before synthesisers and samplers, was mainly experimenting with musique concrète techniques, involving recording sounds from ordinary objects like rulers and lampshades and playing them back at different speeds backwards and forwards, editing them together into pieces of music. Below you can see Delia describing her work in this respect.

Most electronic music of the time was fairly abstract, but as the job of the Workshop was to provide incidental and theme music for BBC television and radio productions, their output tended to be a lot more melodic and accessible. Derbyshire is probably best known today for her realisation – which amounted to co-composition – of Ron Grainer’s theme for the Dr Who television series which launched in 1963. However one could argue that some of her other work was more significant in artistic terms, such as her music for Barry Bermange’s work on the BBC Third Programme. Overall she provided themes and incidental music for over 200 radio and television programmes in the eleven years she worked at the BBC.

She also worked on other projects outside the Workshop, including co-founding the Kaleidophon studio with David Vorhaus and fellow Workshop member Brian Hodgson. The best-known work by this group (known as White Noise) – their first – was the seminal popular electronic music album An Electric Storm (1968) released on Island Records. The trio also recorded material for the Standard Music production music library, Delia composing under the pen-name “Li De la Russe”.

Having been away from the music scene for many years, her interest was rekindled in the late 1990s and she was working on a new album when she passed away as a result of renal failure while recovering from breast cancer.

You can read a fuller account of Delia Derbyshire’s life and work in this Wikipedia article.

![]() Recently Mark Ayres, BBC Radiophonic Workshop Archivist, has been going through the collection of her material held at Manchester University. BBC Radio 4’s Archive On 4 series is presenting a programme on this work, Sculptress of Sound: The Lost Works of Delia Derbyshire, which goes out on Saturday 27 March 2010 at 20:00 GMT.

Recently Mark Ayres, BBC Radiophonic Workshop Archivist, has been going through the collection of her material held at Manchester University. BBC Radio 4’s Archive On 4 series is presenting a programme on this work, Sculptress of Sound: The Lost Works of Delia Derbyshire, which goes out on Saturday 27 March 2010 at 20:00 GMT.

March 24, 2010 Comments Off on On Delia Derbyshire for Ada Lovelace Day

The Digital Economy Bill: an engineer/producer’s view

The Digital Economy Bill now being rushed through the UK Parliament is, in my view, a disaster area of lack of understanding of the issues.

Ordinary people risk disconnection from the Internet — accurately described recently as “the fourth utility”, as vital as gas or electricity to modern life — without due process; sites could be blocked for legitimate users because of alleged infringing content. These are just some of the likely effects of the Digital Economy Bill now being rushed through Parliament in advance of the election. And Swedish research indicates that measures of this type do nothing to reduce piracy.

Pirates will immediately use proxies and other anonymising methods to continue what they’re doing: only ordinary people will be affected. It’s quite likely that WiFi access points like those in hotels, libraries and coffee shops will close down because their owners will not want to be held responsible for any alleged infringement.

This bill will not solve any problems for the industry — in fact it’ll create them. Suppose you send a rough mix to a collaborator using a file transfer system like YouSendIt. It’s a music file, so packet sniffers your ISP will be obliged to operate will, while invading your privacy at the same time, encourage the assumption that it’s an infringement. And you may not be able to access YouSendIt in the first place because UK access has been blocked as a result of someone else’s alleged infringements.

Suppose you run an internet radio station. In the UK that requires two licenses, one from PRS (typically the Limited Online Exploitation Licence or LOEL), and the other a Webcasting licence from PPL. Part of what you pay for the PPL licence is a dubbing fee that allows you to copy commercial recordings to a common library. You might do that in “the cloud” so your DJs — who may be across the country or across the world — can playlist from it, using a service like DropBox. How will the authorities know that your music files are there legally? Do you seriously think they’ll check with PPL? Of course not. It’ll be seen as an infringement, and your internet access could be blocked first, and questions asked afterwards. You’re off the air and bang goes your business. Or you may have already lost access to your library because someone thinks someone else has posted infringing material to the same site.

Worst of all, the bill is being rushed through Parliament without the debate needed to get properly to grips with the issues.

The bill as it stands will threaten the growth of a co-creative digital economy.

The industry badly needs to review its position. We’ve known since the Warners Home Taping survey in the early 1980s that the people who buy music are the people who share music. In my view a business strategy that makes your customer the enemy is not a good one.

The population at large believes that a lot of the figures for illegal file transfer are conjured out of thin air — a recent report claimed that a quarter of a million UK jobs in creative industries would be lost as a result of piracy where in fact there are only 130,000 at present. This does not look good.

The industry has a history of taking the wrong position on new technology. Gramophone records would kill off sheet music sales and live performance. Airplay would stop people buying records (how wrong can you be?). And so on. The industry attitude to new technology seems to be “How do we stop it?” We should instead be asking “How do we use this technology to make money and serve our customers?”

The industry is changing. More and more recordings are being made by individuals in small studios collaborating across the world via the Internet. Sales are increasingly in the “Long Tail” and not in the form of smash hits from the majors. Instead of the vast majority of sales being made through a small number of distribution channels controlled by half-a-dozen big record companies, they’re increasingly being made via individual artists selling from their web sites and at gigs; small online record companies like Magnatune.com; and so on. It’s impossible to count all those tiny micro-outlets, and they are not even recorded as sales in many cases — making reported sales smaller, which is labelled the result of piracy when it’s in fact an inability to count — yet this is exactly where an increasing proportion of sales are coming from. I’ve seen some research from a few years ago even suggested that there was actually a continual year-on-year rise of around 7% in music sales and not a fall at all. And indeed the latest official figures from PRS for Music (of which I’m a member, incidentally) show that legal downloads are more than making up for the loss of packaged media sales — and bear in mind that these numbers may increasingly ignore the vast majority of those Long Tail outlets.

I don’t have all the answers to what we should be doing as an industry. It’s a time of change as fundamental as the introduction of the printing press. The scribes are out of a job — but the printers will do well once they get their act together. Right now we’re in between the old world and the new, and everything is in flux — we don’t know quite what is going to happen.

What I am sure of, however, is that making our customers the enemy is not the way to go. We have to find answers that use the new technology to advance our business and serve our customers, and not pretend that we can force the old ways to return, because if we do, we will all lose.

The Digital Economy Bill in its current form actually strangles the Digital Economy — something we need to help pull us out of recession — rather than supporting it. It stems from old-age thinking and lack of understanding of the technology and its opportunities. It should not be allowed to be rushed through Parliament. Instead it needs an enlightened re-write that acknowledges what is really going on in the world and how we can make it work for us.

If you agree with me, please write to your MP and join in the other popular opposition now taking place.

March 20, 2010 Comments Off on The Digital Economy Bill: an engineer/producer’s view

“…And each slow dusk a drawing down of blinds.”

As readers may know, one of my several activities is audio production, both voice-over work and the production of complete packages with voice, music, effects and so on.

Recently many of these productions have been particularly associated with educational programmes, clients including the British Library and City of Sunderland College. Interestingly, all these projects have resulted from meeting people in the virtual world of Second Life. (Partially as a result, incidentally, I do not have a great deal of time for people who criticise me for “playing” in SL or try to convince me that nothing significant will come of it.)

I have a teaching qualification myself, and I’m particularly interested in the educational possibilities of virtual worlds: Second Life is by far the most popular and widely-used of the virtual worlds currently available, although there is increasing activity in “OpenSim” variants using essentially the same technology.

Most recently I was introduced to some of the staff of the First World War Poetry Digital Archive, based at the University of Oxford. They are on the point of launching (on 2 November) a new region in Second Life (named Frideswide after the patron saint of Oxford) which is home to a painstakingly-built environment designed to shed light on aspects of the life of soldiers in the trenches along the Western Front during the First World War. Students can visit the site and learn not only about the conditions endured by infantrymen during the Great War but also hear poetry from the ‘War Poets’, along with interviews and tutorials.

Here’s how they describe the installation:

This tour of a stylised version of the trench systems in the Western Front has … two objectives:

• to show you the physical context of the trench systems

• to expose items held in the First World War Poetry Digital Archive in a three-dimensional environment…This [is] not an attempt to give you a realistic experience of what it was like to be on the Western Front. The physical depravation, or the chance of serious injury or death, cannot be replicated, and this should always be remembered.

More importantly perhaps, this is but one view of the War – and it would be safe to say this is a view open to discussion. …we have presented rain-sodden trenches, infested by rats, in gloomy surroundings. But this was not always the case. The opening day of the Battle of the Somme, for example, was a beautiful summer’s morning in stark contrast to the depictions we often see of the muddy hell of Paaschendaele.

Chris Stephens, who has been instrumental in putting the simulation together, commissioned me initially to provide an audio version of an A‑level/University-level Tutorial on “Remembrance” along with four poems: Anthem for Doomed Youth by Wilfred Owen, Does It Matter? by Siegfried Sassoon, plus Louse Hunting and Dead Man’s Dump by Isaac Rosenberg.

I’ve now recorded some additional poetry readings – Repression of War Experience, Aftermath, and On Passing the New Menin Gate, all by Siegfried Sassoon; plus 1916 Seen From 1921 and Can You Remember by Edmund Blunden – and an introduction and epilogue.

These poems have a great deal to tell us about the feelings of their authors, and many of them are powerfully moving. Dead Man’s Dump in particular is full of vivid, detailed imagery.

The tutorial, on the other hand, encourages us to ask a number of questions about our conception of what the Great War was like, and uncovers where much of our information has come from. It also challenges some of our assumptions about the conflict. At the time of writing, there are only three veterans of the First World War left alive, so we rely increasingly on indirect sources.

In the Second Life representation, you start off at an army camp and then proceed to the trenches via a floating bubble, during which you hear the introduction to the installation.

Once at ground level in the trenches, you can walk around and visit different aspects of the trench network. Along the way, images of soldiers flicker into view and you might hear an interview or a piece of poetry. The tutorials are accessed via a “HUD” (Head-Up Display) enabling you to proceed through the material and exercises at your own pace. Additional audio extracts are initiated by clicking on loudspeaker symbols.

A scene from the University of Oxford’s First World War representation in Second Life. The visitor is able to walk around in the trenches and ultimately climb a ladder up on to the battlefield itself; the cubes with a loudspeaker symbol on them enable playback of audio material such as poetry readings and interviews. The green-tinged cloud and floating text ahead are part of a section on the use of poison gas during the War.

Overall, the Second Life representation is quite an intense and powerful experience, and I can imagine it will be a particularly effective educational tool.

The challenge for an environment like this is that there is a fairly steep learning curve before visitors can fully experience what a virtual world like Second Life can offer – before you can experience an installation like this you have to learn how to move around, activate things and generally operate successfully in the environment. However in this case you really need to be able to do little more than walk around and click on objects, so most people will require no more than a few minutes of training to be able to get the most out of virtual re-creations like this.

I wish the First World War Poetry Digital Archive every success with this project and am very pleased to have been able to make a small contribution to it. This installation will also be featured in the 10 November edition of the Designing Worlds show on Treet.TV.

*“…And each slow dusk a drawing down of blinds.” is the final line of Anthem for Doomed Youth by World War I poet Wilfred Owen – one of the WWI poems I’ve recorded for this project. Photos courtesy of First World War Poetry Digital Archive.

October 26, 2009 Comments Off on “…And each slow dusk a drawing down of blinds.”

“Radio Drama At A Distance” OpenTech presentation

On 4 July I was pleased to be able to give a presentation at OpenTech, held at the University of London Union, Malet St, on how to create radio drama when the participants are geographically separated. The technique employs VoIP technology (Skype in this case) and the presentation includes an overview of technology choices, how to get the best results, and planning, performance and production tips. Hopefully it will be useful to others interested in developing new approaches to the wonderful field of radio drama.

On 4 July I was pleased to be able to give a presentation at OpenTech, held at the University of London Union, Malet St, on how to create radio drama when the participants are geographically separated. The technique employs VoIP technology (Skype in this case) and the presentation includes an overview of technology choices, how to get the best results, and planning, performance and production tips. Hopefully it will be useful to others interested in developing new approaches to the wonderful field of radio drama.

The presentation is informed by my experiences working with the Radio Riel Players, a group based in the virtual world of Second Life around the radio station Radio Riel.

This presentation is now a Slidecast, including not only the slides but also the audio of my presentation, courtesy of Sam and David at OpenTech. Yes, there are some minor sync issues, but not disruptive ones!

For a more detailed description of the presentation, please see this page.

July 5, 2009 Comments Off on “Radio Drama At A Distance” OpenTech presentation