Category — Music

Gryphon’s ReInvention Reviewed

Gryphon — ReInvention

Reviewed by Richard Elen

The story of the band Gryphon goes back to the beginnings of the 1970s and the London College of Music, when multi-instrumentalists Richard Harvey and Brian Gulland — who were playing Renaissance woodwinds in Early Music band Musica Reservata — got a small group together under the name Spelthorne. Soon the original lutenist left, and Graeme Taylor (guitars and vocals), who had been at school with Harvey, joined the group, swiftly followed by David Oberlé on drums, percussion and vocals. Almost at once the band changed their name to Gryphon after the beast in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland. The band started by playing authentic mediaeval and Renaissance music but soon branched out and started writing their own material. Lawrence Aston, A&R at noted folk label Transatlantic Records, heard the band and signed them. Their first, eponymous album was released in 1973.

The band went on to make three more albums for Transatlantic: Midnight Mushrumps, based around their music for Peter Hall’s National Theatre production of The Tempest; Red Queen to Gryphon Three, and Raindance, the latter which I had the pleasure to record and co-produce in the midsummer of 1975. Various disagreements between the band and the record company resulted in Gryphon moving to EMI’s Harvest label, where they released one album, Treason, in 1977. By this time the band was, as were many high-quality acts of the time, being eclipsed by punk artists who could go out and gig for far less money per night than a complex outfit like Gryphon.

Thus the band became dormant, and so it remained until 2009 when they got together for a reunion concert. By then there had been rumours of a new album in the works, but nothing emerged. Richard Harvey left the band in 2016 to pursue his extensive solo interests, and well-known music library composer and multi-instrumentalist Graham Preskett joined. After a series of concerts a new album, the first for 41 years, was announced: ReInvention, released in September 2018.

The lineup on the album includes original members Gulland, Oberlé and Taylor, with the addition of the aforementioned Preskett, Rory McFarlane on bass and Andy Findon on a range of woodwinds. All the pieces on the album were written by band members: there are no arrangements of traditional pieces here as characterised the first two albums.

ReInvention kicks off with Pipeup Downsland DerryDellDanko — a Gulland title if I ever heard one, which features interweaving recorders with staccato guitar phrases and chords, ultimately joined by pipe organ and saxophone. The piece wanders about lyrically and extremely pleasantly, and you never quite know where it’s going to go next. Out of this North Kent childhood idyll (for such it is), emerge Brian’s slightly avant-garde lyrics. “Stranger things than this have we passed / On our way to you today.” Indeed.

Next up is a piece from Preskett entitled Rhubarb Crumhorn. Yes, all the titles are fairly esoteric, but this piece itself is less so: it’s a very accessible number that builds gently from flute and organ to bassoon and into a fairly stately full band arrangement punctuated by warm Renaissance-sounding chords, and even a little theme reminiscent of something that Richard Harvey might have written. Then it’s off into a brisk gallop through a natty chord progression. Despite being written by relative “new boy” Preskett, this is a classic self-penned (as opposed to trad) Gryphon piece: had it been me sequencing this album, I would have opened the disc with it. There are, however, no crumhorns in this piece.

With A Futuristic Auntyquarian we are back in Brian Gulland territory, with an angular harpsichord-like opening — but only for a moment, as a nicely extended mock-Renaissance woodwind tune takes over, prancing lyrically over the underlying keyboards, to be joined by violin before the track goes off on a pleasant Gullandesque abstract wander with gentle exchanges between the instruments, ultimately joined by drums before going somewhat up-tempo and finally returning to a more robust take on the opening. Nice.

Recall that the band is named Gryphon after the character in Carroll’s Alice, and Graeme Taylor’s ten-minute setting of the poem Haddocks’ Eyes from Looking Glass becomes clear. Gently wandering solo bassoon opens, joined by clarinet and violin for a short trio until joined by acoustic guitar which brings structure to the wandering — and a tune, albeit quite an eccentric one. The piece picks up on the entry of Brian’s vocal, playing the part of the White Knight, in a dialogue with the voice of the Aged, Aged Man, played by Dave Oberlé, with a backing that gently rocks along, with occasional inter-verse returns to the lyrical wandering of the opening until we encounter a rougher solo section two-thirds of the way through, featuring wild heavily distorted and harmonised bassoon. The vocal dialogue gently slows to an apparent end — but it’s not an end at all, it’s a little instrumental romp that returns, finally, to the original gentle theme for the closing lines.

Hampton Caught is another Preskett number, with one of several punning titles to boot. He notes, “It starts somewhere near Sherwood Forest, lurches through harpsichord in three four, a slight hint of boogie in three, then a proper bit of electric guitar, before being interrupted unaccountably by a church organ, some strange rhythms and a build up. It culminates in the three four harpsichord section with additional string as it were.” Couldn’t have put it better myself.

Hospitality at A Price… (Dennis) Anyone For? is, of course, another Gulland number. The sleeve notes describe this as a “genial evocation of the 20s”, and it has some of that ultimately, but in fact it sounds rather like another Carroll poem with the exception of a couple of modern references. And suddenly: jazz crumhorns lead us off into a period piece and a very strange ending.

Dumbe Dum Chit (Preskett) takes its strange name from a mnemonic for a drum pattern to resolve this “bouncy bassoon tune in a strange rhythm”. A neat little number that follolops along, with in fact two strange rhythms rather than just the one, featuring not only bassoon but clarinet and guitar too.

Bathsheba is bass-player McFarlane’s sole composition on the album. Gryphon fans will know Taylor’s style and certainly Gulland’s, and Preskett fits beautifully into the Gryphon tradition, but McFarlane’s is a new voice and a very pleasant one at that. We begin with interweaving fractured phrases from bassoon and clarinet, joined by guitar and drums and, finally, a warm bass part that lasts only a few bars each time around before being joined by violin and woodwinds. One is reminded just a little of the North Sea Radio Orchestra or even the Muffin Men. The sleeve notes outline the controversial Biblical tale.

Sailor V, another by Graham Preskett, begins with a respectably nautical feel (you mean it’s not a pun?) featuring pipes and fiddle, joined by bassoon and guitar. It moves gently and lyrically along until gaining a brasher spring in its step, a touch of the Irish and some odd harmonica flourishes, as the piece moves through some lively changes in the course of its eight minutes to climax with an electric guitar section recapitulating the opening theme, doubled by other instruments in a very Gryphon culmination followed by a gentle wind-down. C’est la vie.

I have a particular fondness for Graeme Taylor’s song Ashes. One of my favourite Gryphon tracks, it was originally written for the 1975 Raindance album, which I engineered and co-produced, but was excluded from the release by the record company for some unknown reason. Its curious tale of afternoon cricket, King’s nephews and stallions, gently and lyrically sung by Brian, is a true joy. Summer that year at Sawmills studio near Fowey in Cornwall was hot, and I decided to record Brian’s vocal (twice), in the open, in stereo, with the mics a fair distance away from him so I caught the birds singing in the background. The version on ReInvention doesn’t have that, but Brian’s performance, albeit not double-tracked, is virtually identical to the original, as is much of the arrangement, though the solos are instrumented differently. Of course I prefer my version, but this one is very, very good 🙂 (You can hear the original on the Collection II album if you can find one.)

The album closes with The Euphrates Connection by Gulland, which begins with a low-pitched recorder theme, picked up by guitar and then a curious, short and unexpected vocal, developing into a complex interweaving multi-part instrumental, laced with Brian’s trademark angular and unexpected figures, a delicious rocky interchange between guitar, pipe organ and other instruments leading to a repeating sequence of short pipe organ chords, adorned only by reverb and the occasional sonority, before being joined by solo flute, bass, violin and guitar fragments and fading gradually to an end.

And so ends Gryphon’s first new album for over forty years. It’s beautifully recorded and produced by Graeme Taylor in his “Morden Shoals” studio: the overall sound is excellent and well-captured with a great deal of detail and care. The musicianship is of a uniformly high standard throughout and even the most complex angular and avant-garde passages are confident, sure-footed and executed with aplomb.

There are few artists who could return to the scene after four decades to such acclaim as Gryphon, as if their return has been awaited by us all for the entire time they were away. ReInvention provides exactly what it says, the band reinventing itself with new members and new directions. Unmistakeably Gryphon, it develops musical directions that were hinted at in earlier albums, takes them forward, and delivers an ultimately satisfyingly and eclectic result. One can only hope that it is the first in a series as Gryphon moves forward to new musical heights following its re-formation.

October 19, 2018 Comments Off on Gryphon’s ReInvention Reviewed

More Gryphon Restoration

As I noted previously, there are some technical challenges associated with recovering the recordings of the band Gryphon that I made in July 1974 during their landmark performance at the Old Vic.

A notable problem was the fact that there was a bass DI in the main PA mix (which was the basis for the recording, with the addition of a coincident pair of ambient mics) and this was often extremely loud in the balance — sometimes enough to cause intermodulation distortion with the rest of the mix (it’s possible that this was overloaded on the recording).

To give you an insight into the results of this factor, here’s another piece from the Old Vic tapes. This is Opening Number, the band’s, er, opening number. Note the effect of the bass entry about half-way through.

This is an example of why it may not be possible to get an album’s worth of tunes out of this recording. However it will be worth our trying to recover the stereo master tapes to see if the distortion is on there too (these transfers are from a copy).

August 21, 2018 Comments Off on More Gryphon Restoration

Restoring an Ancient Gryphon

This month has seen the release of the new album by old friends of mine, Gryphon. The album, ReInvention, is their first for 41 years: the band, re-formed and augmented, though now without the presence of co-founder Richard Harvey, is poised, at the time of writing, to perform the new album in the Union Chapel.

In honour of the new release I thought it might be interesting to attempt to resurrect what is the first recording I ever made of the band (I was their sound engineer in the studio and on the road from 1974–5, culminating in the recording of the Raindance album across Midsummer 1975, which I engineered and co-produced). This was a recording of the live performance given at the Old Vic on 14 July 1974 – the first and, I believe the only, rock concert ever to have been held at the Old Vic or hosted by the National Theatre. Gryphon had recently been commissioned to write the music for Peter Hall’s National Theatre production of The Tempest, which had premiered on March 5, and had recorded their second album, Midnight Mushrumps (a reference to Prospero’s speech, 5.1.39) including a suite based on the music for the play, with Dave Grinsted at Chipping Norton Studios in the Cotswolds.

The Old Vic performance was right at the start of my involvement with the band and I was yet to be responsible for their sound live or in the studio. However for the occasion of the Old Vic performance I was able to obtain a Teac 3340 4‑track recorder and situated it beside the mixing desk on the balcony. I had a pair of AKG D‑202s, excellent all-round dynamic mics, arranged in a coincident pair as close to the centre of the balcony as I could get, and recorded these on one pair of tracks on the Teac; and in addition I put a stereo feed from the board on the other two tracks. The resulting 4‑track tape gave me a clean feed of the PA mix, with the addition of audience reaction and ambience from the room mics – particularly effective on the percussion. However as we were on the balcony there was a delay between the PA feed and the room mics, so when I mixed-down the 4‑track to stereo I put a delay on the PA feed tracks to bring them into sync with the room mics. This also gave me the opportunity for a little fun, as I could vary the delay slightly to give a slight flanging effect on tracks like Estampie, which Richard Harvey refers to in the intro as “a mediæval one-bar blues”, an effect which had been used on the original album recording for a similar purpose.

The disadvantage of the PA feed was that it included a bass DI run at considerable level, and as a result, Philip Nestor’s bass-playing features prominently in the feed. So much so, in fact, that the bass causes some intermodulation distortion with other instruments, rendering some of the pieces sadly virtually unusable. However with some judicious use of EQ around the 80–200Hz mark the bass can be quietened-down enough for a reasonable balance to be achieved in many cases.

Sadly the original 15in/s mixdown master of this recording is lost, and believed to be in Los Angeles. However I made a cassette copy of the three reels which I hung on to. They were BASF Chrome cassettes and I recorded them with a Dolby B characteristic on a machine that I had evidently been able to set the Dolby level on correctly as the results are quite respectable. For these experiments I transcribed the cassettes from a Technics M260 kindly provided by Duncan Goddard, who is a highly talented restorer of vintage analogue recorders, having previously supplied my trusty ReVox PR99 and A77.

I digitised the audio via a Focusrite Scarlett interface and brought it into Adobe Audition, my DAW of choice for stereo audio production. I cleaned up the noise floor with Audition’s built-in noise reduction tools and a couple of Wave Arts restoration plug-ins, using the Audition parametric EQ to restrain the bass end. Here’s an example of the results: the mix of Estampie referred to above. And I hope you like it.

August 20, 2018 Comments Off on Restoring an Ancient Gryphon

Gryphon At Bilston

Just over a year after seeing the re-formed Gryphon at The Stables near Milton Keynes, I was lucky enough to catch them live at the Robin 2, a cavernous West Midlands venue somewhat reminiscent of somewhere like the Station Inn in Nashville, in one of a short series of live gigs culminating in a performance at the gorgeous Union Chapel. Sadly I couldn’t make the latter, but it is being professionally video-recorded so hopefully we’ll all be able to see it at some point.

A Brief Historie

For those of you who don’t know the band — and if you do, you can skip to the section headed Robin 2 below — Gryphon was formed in the early 1970s and was a kind of crossover act merging mediaeval and Renaissance music and instruments, with bassoon, flute, guitars, percussion (and ultimately drums) and bass for an effect that varied from folk music to rocked-up Early Music to something approaching Prog Rock. A truly marvellous combination, I assure you, as any of the five albums produced in the 1970s (and all still available, along with various collections of previously unreleased tracks and broadcast performances) will attest.

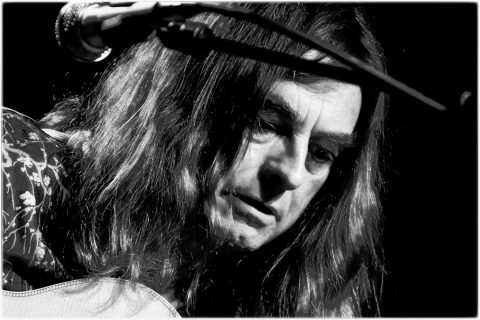

At the heart of the band were two people I went to school with (albeit two years below me), multi-instrumentalist Richard Harvey and guitarist Graeme Taylor, one or other or both of whom, often with Brian Gulland, penned much of the original material that appeared on the albums such as the characteristic intricate instrumental suites (Juniper Suite on their eponymous first album, for example, being credited Taylor-Harvey-Gulland) and longer works while Taylor wrote often delicate, finely-wrought instrumentals and songs with wildly punning and semi-obscure lyrics. The other band members contributed their own material too, to great effect, and combined with their settings of traditional songs and dances, Gryphon was entirely unique. I was lucky enough to tour with the band for a year as their sound engineer, live and in the studio (1974–5, including US and UK tours supporting Yes as well as college gigs, culminating with the recording of their fourth album, Raindance, which I also co-produced).

The band was effectively wiped out by the changes in British popular music in the mid-70s that resulted in instrumental virtuosity — or indeed almost any level of musical ability above that of a member of the audience — being deprecated. Thankfully the albums never really went away, and even the unreleased tracks appeared on Collection CDs in due course (including several from Raindance, which was essentially cut to ribbons by the record company, omitting a few gems).

Reformation

Everything seems to come around again these days, and over 30 years after their final live appearance, the band re-formed in June 2009 for a sold-out reunion concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on London’s South Bank featuring the original core membership of Richard Harvey (woodwinds, keyboards), Brian Gulland (woodwinds, keyboards, vocals), Graeme Taylor (guitars, vocals), and Dave Oberlé (percussion and vocals). They were joined by Jon Davie — the bass-player from the band’s fifth album, Treason — and new arrival, talented multi-instrumentalist and veteran music library/film composer Graham Preskett on a varied collection of keyboard and stringed instruments.

Everyone hoped that the one-off reunion would be followed by a tour, but it was not until 2015 that this actually got off the ground with a relatively short series of gigs — all of which were extremely well attended and showed that the band had lost none of its vigour and originality. Indeed, the presence of Preskett at last made it possible to perform works that had been impractical to play live previously, such as Juniper Suite.

The hope was that there would be additional dates in 2016 and this indeed came to be, but, it transpired, without the presence of Richard Harvey, who announced in the Spring that he would be leaving the band due to a cramped schedule and to pursue his own multi-faceted career. And indeed it is, with a major tour with Hans Zimmer and many other activities on the horizon.

Robin 2

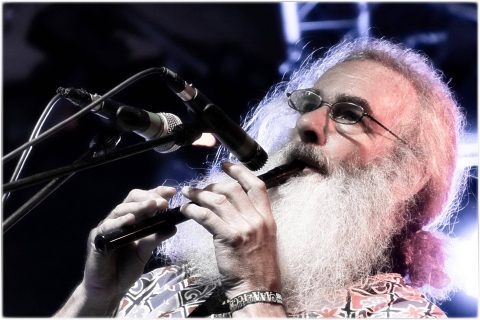

(Most of) Gryphon at Bilston, August 14 2016. L to R: Keith Thompson, Dave Oberle, Graeme Taylor, Rory McFarlane, Brian Gulland. Where’s Preskett? Photo by Paul Lucas

As a result, the band that has been touring in 2016 has some changes in lineup. Preskett is in there — he is a major asset — and on bass we find Rory McFarlane, a talented session musician and composer who has also plenty of band experience with Richard Thompson. It would be silly to say that “Richard Harvey’s place in Gryphon has been taken by Keith Thompson”, because Keith is an extraordinarily talented Early Music woodwind specialist in his own right with a history going back to the 1970s and including the exceptional City Waites: he brings to the band a level of talent and expertise that is extremely impressive. The combination of musical skills represented by this incarnation of the band is unsurpassed and delivers the instrumental fireworks we might expect from a group of musicians who are all at the peak of their powers.

And thus, finally, to the Robin 2 gig. The performance fell into two sets and followed a similar structure to the gigs of 2015, with primarily pieces from the first album in the first half — Opening Number to begin with, followed by Kemp’s Jig, The Astrologer (with an amusing contest of vocals between Gulland and Oberlé), and the aforementioned Juniper Suite. Next up was The Unquiet Grave, to which Brian Gulland gave an interesting introduction, mentioning Vaughan Williams’ Five Variations on Dives and Lazarus, which employs the same tune, while The Unquiet Grave itself is often heard with a different melody. I always wondered about that… The set was rounded off by Dubbel Dutch from the Midnight Mushrumps (second) album and Estampie from the first.

Later material permeated the second set, leading off with a medley from the third album, Red Queen to Gryphon Three with its chess references. Second up was the Graeme Taylor-penned and atmospheric Ashes, originally removed from the fourth album, Raindance, to my distinct annoyance, and one of my favourites of the band’s songs. And they very kindly gave me a shout-out for the track, which was most kind! The performance was complete with birdsong: when we recorded the track originally, in the hot midsummer of 1975, I recorded Brian Gulland’s vocals outside in the open with a stereo pair of mics, with him standing far enough away that I could crank up the gain and capture the natural birdsong. Further pieces in the set included more from the first album, some dances originally written by High Renaissance German composer Michael Praetorius for his enormous set of dances known as Terpsichore (and which, we should note, are yet to be recorded, hint hint..), Lament from the third album and rounding off with the thunderous romp that is Ethelion from the second album. An encore consisted of a very amusing combination of tunes leading off with Le Cambrioleur est dans le Mouchoir, (a strange little piece from Raindance, co-written by Taylor and bass player of the time Malcolm Bennett) followed by a touch of Preskettised Gershwin and then Tiger Rag.

The overall performance was excellent and particular credit needs to be given to Keith Thompson, new to the band and with only one previous live performance with the band under his belt at this point. Gryphon has an unusual, if not actually unique, combination of what would traditionally have been called “loud” and “soft” instruments. In addition to being difficult to get a live sound balance on, as I know from my own experience, the stage monitoring is particularly tricky, and Keith was sandwiched between Graham Preskett on one side and Graeme Taylor on the other, neither of whom are likely to have been particularly quiet in the monitors. Despite this, and a cavernous hall with a huge and venerable PA that was really designed for out-and-out rock bands that swallowed him a little from time to time, Keith’s performance came across as lively and exciting and full of virtuosity.

Keith and Brian Gulland therefore handled the woodwinds ancient and modern, in the same way as Harvey and Gulland would have done in earlier times; but in addition the keyboard axis was between Brian and Graham Preskett, with Preskett also contributing fiddle and other stringed instruments. The multi-instrumental interplay between the three of them was one of the most interesting aspects of this new lineup and I am sure that they will only become even tighter and more dazzling as they work longer together. Meanwhile, Graeme Taylor’s guitar expertise seems only to increase every time I hear him — and while we’re on the subject of Graeme, don’t miss the latest release from his ‘other’ band, Home Service, whose new album A New Ground is definitely worth a listen. Brian Gulland, meanwhile, continues his endearing hirsute antics on stage, and on this occasion handled a good deal of the introductions, and in some cases — The Unquiet Grave referred to above for example — we learn more about the numbers, which is a good thing in my view, as long as it’s not too extensive (which it wasn’t).

Dave Oberlé was excellent throughout, not only on drums/percussion but on vocals too, where his style suits the material down to the ground. From where I was sitting, I couldn’t actually see bassist Rory McFarlane but I could certainly hear him, providing a solid bottom end to the sound and always spot-on with timing. You can’t really think of Gryphon as having a “rhythm section” as such, as Oberlé’s role is generally more percussion than drums, but McFarlane underlines the importance of good lively yet solid bass playing with this material.

Overall, then, an exceptional performance and one that bodes very well for the future, as the band evidently intend to stick around. As I noted at the top, the Union Chapel gig is being video recorded, and I hope to see that released at some point. And there is even talk of an album in the works — 40 years after the last one. Excellent going.

September 12, 2016 Comments Off on Gryphon At Bilston

Gryphon at The Stables

Wednesday May 13th saw a performance by Gryphon at the Stables near Milton Keynes. The gig was one of a relatively brief series of performances under the banner “None the Wiser” that the band, originally active in the 1970s, re-formed to give.

The personnel on the tour represented a fair approximation to the original lineup of Brian Gulland (bassoon, Renaissance woodwinds, vocals and a touch of keyboard), Jon Davie (bass), Dave Oberlé (percussion and vocals), Graeme Taylor (guitars), and Richard Harvey (keyboards, woodwinds, mandolin, clarinet, Renaissance woodwinds, dulcimer, ukulele, flute), augmented by an additional talented multi-instrumentalist and composer in the form of Graham Preskett (keyboards, violin, 12-string guitar, viola).

The tour culminated with a performance at the Union Chapel in London, which I would love to have attended: the picture above (by Julian Bajzert, used by permission) was taken there (the band appears almost in the order listed above, but with Richard Harvey far right).

The Stables, not a location I’ve visited before, is an impressive venue, although perhaps best suited to theatrical work. The stage layout required the PA to be placed perilously close to the band – and to Richard Harvey in particular – which mean that a number of high-gain mics were pointing more or less directly at the PA. Speaking from experience as Gryphon’s sound engineer (live and in the studio, during 1974–75) the band is tricky to mix at the best of times, with its unique combination of “soft” and “loud” instruments (as they would have been called in the Renaissance period) and a nearby PA no doubt made the mix at the Stables difficult in the extreme.

For those who have not encountered Gryphon previously, the band began in the early 1970s when Royal College of Music graduates Richard Harvey and Brian Gulland started as a duo playing traditional English folk with Renaissance and mediaeval tendencies. They were soon joined by guitarist Graeme Taylor and percussionist Dave Oberlé, and then by bass-players Philip Nestor, Malcolm Markovich, formerly Bennett, and finally (1975–77) Jonathan Davie.

Their first (eponymous) album, recorded in 1973 by Adam Skeaping on 4‑track in a tiny studio in Barnes, combined lively approaches to traditional songs flavoured with recorders and crumhorns — earning the band a “Mediaeval Rock” label — with some original material by Harvey.

Their first (eponymous) album, recorded in 1973 by Adam Skeaping on 4‑track in a tiny studio in Barnes, combined lively approaches to traditional songs flavoured with recorders and crumhorns — earning the band a “Mediaeval Rock” label — with some original material by Harvey.

The second album, Midnight Mushrumps (1974), featured a side-long suite based on the band’s music for Sir Peter Hall’s The Tempest at the Old Vic. The third, Red Queen to Gryphon Three (also 1974) featured a 4‑part suite theoretically based on a game of chess. This was followed by Raindance in 1975 and finally, following a move from Transatlantic Records to EMI/Harvest, Treason in 1977 – after which the band was sadly eclipsed, as were many talented British artists at the time, by so-called “new wave” artists who eschewed instrumental virtuosity.

I was lucky enough to work with the band as their sound engineer on the road and often in the studio, covering a college tour in mid-1974, the US 1974 and UK 1975 tours as support band to Yes, and culminating in recording and co-producing Raindance at Sawmills studios in Golant, Cornwall, across midsummer 1975.

I was lucky enough to work with the band as their sound engineer on the road and often in the studio, covering a college tour in mid-1974, the US 1974 and UK 1975 tours as support band to Yes, and culminating in recording and co-producing Raindance at Sawmills studios in Golant, Cornwall, across midsummer 1975.

There had always been hopes in several quarters that some incarnation of the band would get back together at some point, and the outfit has always had a loyal and extensive internet following. The albums are all available, along with additional albums covering BBC sessions and “lost tracks” (such as those we recorded for Raindance but were not allowed by the record company to include on the album — yes, it still annoys me). Hopes for a reunion were granted in 2009 with a one-off concern at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London which was exceptionally well-received, and saw the addition to the lineup of composer and multi-instrumentalist Graham Preskett for the first time.

The May 2015 tour, in preparation for some time, was relatively limited in extent but did enable a good many people to get to one of the very well-attended performances.

The first half of the Stables performance consisted primarily of pieces from the first album – kicking off, appropriately enough, with Opening Number, followed by the cautionary tale of The Astrologer with vocals by Oberlé in fine form, then an instrumental mélange of the traditional Kemp’s Jig and a mediaeval Estampie. This was followed by the band’s rendering of a personal favourite, also with vocals by Oberlé , The Unquiet Grave, an English folk song (Child Ballad 78) dating back to around 1400 in which a young man mourns his dead lover to a somewhat excessive degree, to which Gryphon add a particularly eerie middle section. Listeners to this piece with a classical background may note that the tune Gryphon use for this song (several tunes have been used traditionally) is also commonly associated with Dives & Lazarus (Child Ballad 56 – see Vaughan Williams’ variations on this theme).

Next up was a rendering by Graeme of his solo piece, Crossing the Stiles. All Graeme’s pieces for the band were tricky in one way or another and often complex, and hearing him perform this, one can only conclude that his guitar virtuosity has somehow increased over the years: his playing was exceedingly impressive.

It was followed by what I believe was the first live performance of Richard Harvey’s original composition from the first album, and the track that turned me on to the band all those years ago, when a friend played me this unknown track he had recorded from a John Peel programme: Juniper Suite. If it hadn’t been noticeable earlier in the set, it rapidly became clear here how beneficial the addition of Graham Preskett to the original lineup has been: the presence of extra keyboard resources, for example, freed Richard Harvey to focus more on his world-leading woodwind expertise, and made doing pieces like Juniper Suite live possible. Preskett, like Harvey, is also an excellent multi-instrumentalist, and the addition of violin and viola, for example, made quite an impressive difference at times, adding textures that were not previously part of the Gryphon sound but that fitted in exceptionally well.

During the course of the first set we also enjoyed some surprisingly ‘basso profundo’ vocals from Brian Gulland as well as his woodwinds and organ work. The ensemble piece Dubbel Dutch – a miniature suite in itself – from the second album closed the first half.

During the course of the first set we also enjoyed some surprisingly ‘basso profundo’ vocals from Brian Gulland as well as his woodwinds and organ work. The ensemble piece Dubbel Dutch – a miniature suite in itself – from the second album closed the first half.

The second half opened with a version of Midnight Mushrumps in all its album-side length glory, that often sounded pretty much exactly as it did when I mixed it live myself over 40 years ago.

The band then played one of my favourite ‘lost’ tracks, Ashes, which we originally recorded at Sawmills in 1975 for the Raindance album but which never made it on to the disc – and to my great surprise and pleasure, Brian very kindly dedicated it to me, which was extremely heart-warming. Thanks, guys! (The original recording is on the second Collections disc if you want to check it out.)

The set continued with a couple of excerpts from Red Queen to Gryphon Three – one based on Lament and then a medley of other themes from the album, all of which were expertly performed throughout, with plenty of Harvey recorder twiddly bits and some great bass-playing from Jon Davie, while Dave Oberlé fired off impressive rounds of percussion as appropriate. Indeed, the phrase ‘virtuouso performances’ can happily be applied to everyone in the band and to the whole set.

The set continued with a couple of excerpts from Red Queen to Gryphon Three – one based on Lament and then a medley of other themes from the album, all of which were expertly performed throughout, with plenty of Harvey recorder twiddly bits and some great bass-playing from Jon Davie, while Dave Oberlé fired off impressive rounds of percussion as appropriate. Indeed, the phrase ‘virtuouso performances’ can happily be applied to everyone in the band and to the whole set.

Encores included a marvellous new suite of rocked-up Renaissance dances of the kind for which Gryphon are perhaps traditionally best-known, outclassing even the likes of The Bones Of All Men and in this case relying quite a bit on Michael Praetorius’s Terpsichore, followed by a remarkable piece that, starting off from a certain Cambrioleur (Le Cambrioleur est Dans le Mouchoir, from Raindance), wove together several disparate threads including George Gershwin’s Promenade (Walking the Dog), and featured some exquisite clarinet work from Harvey, exchanging rapid-fire lines with Preskett, to end with a spirited interpretation of the very early 20th century jazz standard Tiger Rag.

Overall, I found it a magnificent and quite magical performance from everybody concerned.

Main image: Gryphon at Union Chapel, London, May 2015, by Julian Bajzert, used by permission. L to R: Brian Gulland, Jon Davie, Dave Oberle, Graeme Taylor, Graham Preskett, Richard Harvey

August 3, 2015 Comments Off on Gryphon at The Stables

What is authenticity?

My attention was drawn to a rather interesting article in the Washington Post late last year on the use of “historical” FX in the movie “Lincoln”. Spielberg actually tried very hard to capture “authentic” sound effects — Lincoln’s actual pocket watch ticking, the ring of the bell of the church he attended, and so on.

Quite a lot of the time, in my experience, recording actual sounds doesn’t give you as effective a result as faking it with something else, but with sounds like those mentioned in the article, you can see why it might be worth chasing the originals. Apart from the fact that people notice when details are wrong — the BBC used to get letters if they used the sound of the wrong vintage plane in a radio play, for example, and they probably still do — there’s an interesting philosophical dimension here, about what we mean by “authentic”.

In the days of phonographs and cylinders, it was common to make recordings of famous people making famous speeches and other spoken material. Very often these were not recorded by the actual person claimed. But the degree of “realism” — or may we say “authenticity” — was judged by how well the performer represented the original person, not by whether or not it was the original person making the recording.

Similarly, we can read reviews of Clément Ader’s historic stereo relays from the Paris Opera House to the World Expo in Paris in 1881 and be surprised that listeners found the experience of listening to a pair of early moving-coil telephone earpieces fed by carbon microphones down hundreds of metres of wire so realistic. Surely it was nothing like hi-fi as we know it.

Exactly what we mean by “authenticity” has certainly changed over the years. And there is a distinct difference between accuracy and experience. When I’m in the studio, I try to do my best to ensure that the listener at home or on the move hears as close as possible to what we heard in the control room when we played back the master mix and said “That’s the one”. Is this a reasonable thing to seek to achieve? Or should we be striving to give people the best experience, regardless of authenticity? I touched on this the other day referring to miming at the Presidential Inauguration: definitely a case of going for the best experience.

To me, you can apply the old slogan “The closest approach to the original sound” to any recording as long as you know what you mean by the “original sound”. In my opinion this is generally the master playback, not what it sounded like out in the studio. In the case of multitrack layered popular music this is obviously the case. But how about a recording of a string quartet? Are you trying to give people the audio experience they would hear in a concert hall (I say “the audio experience” because you would be missing all the non-audible cues), or are you trying to give them the experience you had when you signed off the master playback? Well, probably, the latter.

It would be worth pointing out that listening to concert-hall recordings is frequently not very much like being there, because you only hear the music. Even if you recorded the concert Ambisonically, captured the entire soundfield and played it back faultlessly, you would only have captured the audio of the event, not the experience. This being the case, what is often done is to make the recording more lively and exciting to make up for the non-audio aspects of the performance. Close mics, changes of dynamics, and other techniques do make the playback more involving. In my opinion there is nothing wrong with this as long as it’s not dishonestly presented. Once again, the original sound is what’s heard in the control-room, not in the concert-hall — and that’s what you should be wanting people to hear at home.

It’s all very well claiming to reference playback systems to the sound of actual musical instruments, but that begs all kinds of — generally unanswerable — questions about how you established the sound of the instruments in the first place. What was your reference? Where did you hear them? How far away were you? Who was playing what? What was heard in the studio on master playback, however, is a perfect reference: it’s what the production team thought was the best representation of every aspect of the music, the composer, the artist and the performance — and more. They regarded it as the best communication between all those factors and the person listening to the recording. And, in my opinion, it’s the only thing you can reasonably expect to try to recreate for the listener.

For a further consideration of the philosophical implications of “authenticity”, in the context of “Lincoln”, check out this blog post.

February 1, 2013 Comments Off on What is authenticity?

On Delia Derbyshire for Ada Lovelace Day

Today, March 24 2010, is Ada Lovelace Day, the day when we celebrate women in science and technology and their achievements – typically by blogging about them. You can find out more about Ada Lovelace Day at the Finding Ada web site, but here’s the basic gist:

Ada Lovelace Day was first celebrated in 2009, when over 2,000 people blogged about women in technology and science and the event receive wide media coverage. This year the hope is to get 3,072 people to do the same. Ada Lovelace Day is organised by Suw Charman-Anderson, who writes:

“Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace was born on 10th December 1815, the only child of Lord Byron and his wife, Annabella. Born Augusta Ada Byron, but now known simply as Ada Lovelace, she wrote the world’s first computer programmes for the Analytical Engine, a general-purpose machine that Charles Babbage had invented.”

And there’s plenty more where that came from.

The marvellous logo shown above was created by Sydney Padua and Lorin O’Brien and appears on the former’s wonderful 2D Goggles comic web site.

Delia Derbyshire

I’ve been interested in electronic music for decades, and I suppose one of my greatest influences was the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, sadly disbanded in March 1998 during the era of the BBC “internal market” under Director-General John Birt, when departments had to operate at a profit or close. This resulted in absurdities like it becoming cheaper to nip down the street from Broadcasting House to HMV in Oxford Street to buy a CD containing a piece of music to use in a programme rather than obtaining the track via the BBC Record Library.

Delia Derbyshire (1937–2001) was born in Coventry, my home town, and completed a degree in mathematics and music at Girton College Cambridge. In 1959, she famously applied to Decca to work at their recording studios in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead and was turned down, being told that they didn’t employ women.

After a stint with the UN in Geneva and with music publisher Boosey and Hawkes she joined the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in 1962, which, in those days before synthesisers and samplers, was mainly experimenting with musique concrète techniques, involving recording sounds from ordinary objects like rulers and lampshades and playing them back at different speeds backwards and forwards, editing them together into pieces of music. Below you can see Delia describing her work in this respect.

Most electronic music of the time was fairly abstract, but as the job of the Workshop was to provide incidental and theme music for BBC television and radio productions, their output tended to be a lot more melodic and accessible. Derbyshire is probably best known today for her realisation – which amounted to co-composition – of Ron Grainer’s theme for the Dr Who television series which launched in 1963. However one could argue that some of her other work was more significant in artistic terms, such as her music for Barry Bermange’s work on the BBC Third Programme. Overall she provided themes and incidental music for over 200 radio and television programmes in the eleven years she worked at the BBC.

She also worked on other projects outside the Workshop, including co-founding the Kaleidophon studio with David Vorhaus and fellow Workshop member Brian Hodgson. The best-known work by this group (known as White Noise) – their first – was the seminal popular electronic music album An Electric Storm (1968) released on Island Records. The trio also recorded material for the Standard Music production music library, Delia composing under the pen-name “Li De la Russe”.

Having been away from the music scene for many years, her interest was rekindled in the late 1990s and she was working on a new album when she passed away as a result of renal failure while recovering from breast cancer.

You can read a fuller account of Delia Derbyshire’s life and work in this Wikipedia article.

![]() Recently Mark Ayres, BBC Radiophonic Workshop Archivist, has been going through the collection of her material held at Manchester University. BBC Radio 4’s Archive On 4 series is presenting a programme on this work, Sculptress of Sound: The Lost Works of Delia Derbyshire, which goes out on Saturday 27 March 2010 at 20:00 GMT.

Recently Mark Ayres, BBC Radiophonic Workshop Archivist, has been going through the collection of her material held at Manchester University. BBC Radio 4’s Archive On 4 series is presenting a programme on this work, Sculptress of Sound: The Lost Works of Delia Derbyshire, which goes out on Saturday 27 March 2010 at 20:00 GMT.

March 24, 2010 Comments Off on On Delia Derbyshire for Ada Lovelace Day

Connect or Die: New Directions for the Music Industry

Here’s a brilliant slide presentation posted on Slideshare by Marta Kagan, who’s the managing director of the Boston office of Espresso, an integrated marketing agency based in Toronto and Boston.

I don’t think this presentation has all the answers (none of us do, I’d suggest), but there are some excellent observations, starting points and, above all, practical strategies. I made the following comment on the Slideshare page:

Excellent. While I might be concerned about the power the Live Nation/Ticketmaster combo could have over the live environment, I have no doubt that the fundamental thrust of your presentation is correct.

The challenge for the majority of musicians working today has to be ‘How do I make any money from music?’ In a world that echoes the days of the development of the printing press, where the scribes are already losing their jobs but nobody’s quite sure how this new print-based world will pan out, we need all the ideas we can get. We’re building the new world as it happens and there’s a lot to try.

For years the music industry has opposed new technology: its question has been ‘How can we stop people doing this?’ when it should have been, and should be, ‘How do we make money from this by giving our customers what they want?’

You’ve provided, if not the answers to that question, at least a way towards them. Thank you!

March 22, 2010 Comments Off on Connect or Die: New Directions for the Music Industry

Ballet mécanique in Cambridge

On Sunday last I had the almost unique opportunity to attend a performance of George Antheil’s Ballet mécanique at the West Road Concert Hall in Cambridge, part of the Cambridge Music Festival. The concert also marked the 100th anniversary year of the publication of the Futurist Manifesto.

My attention was drawn to the event by my friend Paul Lehrman, whom I knew originally as a brilliant journalist who used to write for me when I was Editor of Studio Sound back in the 1980s. Since then we’ve done a bunch of stuff together including music for KPM Music Library and much more.

Today, Paul is a music professor based at a university in the Boston area, and he has made quite a name for himself for his realisation of a version of Antheil’s work which calls (at least in its full version) for a percussion orchestra of three xylophones, four bass drums and a tam-tam (gong); two live pianists; seven or so electric bells; a siren; three aeroplane propellers; and 16 synchronized player pianos. As you can imagine, it’s a flamboyant, controversial, downright noisy piece of avant-garde music.

This large-scale version of the piece, composed around 1923, was never performed in Antheil’s lifetime, apparently because the friend of Antheil’s who told him you could sync up 16 player pianos was wrong: the technology of the time did not allow it. Paul Lehrman, however, was commissioned by music publishers G. Schirmer to realise the work for the 16 player pianos called for in the original manuscript, using modern digital technology in the form of digital player pianos, MIDI, and samples for the aircraft propellers.

This he did, and the first performance took place at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, exactly ten years ago (on 18 November, 1999). Since then it’s been performed on numerous occasions around the world. You can read more about it, and about Antheil, at Paul’s site which you can find here at antheil.org.

This was not the version performed at West Road on Sunday, however. That was a somewhat more restrained version performed on this occasion on a single Pianola plus two live pianists, three xylophones, drums and percussion, rattles (performing the propeller parts), two electric doorbells and a hard-cranked siren. Musically, it was a version first performed in 1927 (and not very often thereafter). Paul asked me if I could go along and interview Paul Jackson, the conductor, experience the performance and find the answers to some questions about this particular version.

This sounded as if it could be enormous fun (which indeed it was) so I duly turned up for the event, Music hard and beautiful as a diamond, part of the 2009 Cambridge Music Festival, consisting of three works performed by Rex Lawson on Pianola, Julio d’Escriván on iPhone, the Anglia Sinfonia, Anglia Voices and MEME, conducted by Paul Jackson.

The concert itself was preceded by a 45-minute presentation by Lawson and d’Escriván about the Pianola and the iPhone as an instrument respectively (d’Escriván’s piece started the evening). I was particularly interested in Lawson’s exposition on the Pianola.

The Pianola is quite different from the Reproducing Piano and is not even truly the stuff of “player pianos” in saloons in cowboy movies, though they all use a “piano roll” to provide the notes. In the case of the Reproducing Piano, the roll contains not only the notes but all the tempo, expression and other aspects of an actual performance. Thus the big selling point of these systems, therefore, was to get famous performers and composers to perform their works, which could then be flawlessly reproduced at home.

The Pianola, on the other hand, began life as a “cabinet player” – a box on castors that you wheel up to a conventional piano (a Steinway grand in the case of the Sunday performance) and lock into place so that its felt-covered actuators can press the keys. It’s powered by pedals, which drive the roll and also force air through the holes in the roll to sound the notes. By changing the pressure on the pedals (eg by stamping on them) you can also change the loudness of the notes – in other words, give the performance dynamics – that can be applied to different parts of the range. There’s also a tempo slider – and even technology that picks out the top line automatically.

This is all rather important, because the piano roll for a Pianola contains only the notes – the player determines the tempo and expression (in a solo performance, for example, including visual cues printed or written on the roll). Thus a Pianola performance actually is a performance, and not a playback. Yes, the notes are provided, but the expression is manually applied.

Pianola rolls were not created by playing the instrument and recording what the performer did, as in the case of the Reproducing Piano. Instead, they were created simply from the score. Imagine a MIDI sequence created in step-time with no velocity information and you get the idea.

Most people couldn’t be bothered to learn the subtle nuances of Pianola performance, however, and simply pedalled away, giving the instruments a rather lifeless, mechanical reputation which was entirely undeserved. Ultimately, mechanisms were built into (usually upright) pianos – and hence the player pianos in the bars depicted in the cowboy movies aforementioned.

Rex Lawson, who performed the Pianola part in Sunday’s concert, is a leading expert on the instrument, and his presentation disposed of quite a few myths, especially when it came to the performance of Ballet mécanique. The fact that the player controls the tempo means that the Pianola can actually follow a conductor in the conventional way – the Pianola does not have to set the tempo and have every other player sync to it. In Paul Lehrman’s performances, in contrast, the MIDI replay system that drives the player pianos also generates a click track that everyone follows.

Similarly, the fact that you can control the dynamics of the Pianola means that the instrument does not simply bash out all the notes at full blast. As a result, primarily, of these two factors, Ballet mécanique takes on a whole new degree of light and shade. Yes, it’s still a cacophony of 20s avant-garde exuberance, but it takes on a good deal of additional subtlety.

Lawson feels that the piece is designed to be played on these Edwardian instruments rather than modern digital systems, and that you need to actually perform the Pianola part – as he puts it, you need to “sweat”. However, he is interested in getting some fellow Pianola-owning friends together to perform the work on four Pianolas synchronised as far as tempo is concerned.

Lawson thinks the idea of 16 player pianos was Antheil showing off, that it was probably originally intended for four live pianists, and that the big problem with performing it at the time was that there were not nearly enough players in Paris who knew the subtleties of the Pianola and how to use its tempo and expression capabilities. In his planned 4‑Pianola performance, he would set the tempo at his Pianola and the others would follow the tempo he set by using stepper motors to sync them to his unit. Which sounds like a great idea, though there might be issues due to stretching or slippage of the rolls: it might need sprocketed piano rolls, which did actually exist.

The Sunday performance of the single-Pianola version used three piano rolls, and to allow changing them the performance was split into three movements.

The performance, for me, shed new light on a fascinating composition from the 1920s. A radically different interpretation from Paul Lehrman’s, it suggests interesting possibilities for a Lawson/Lehrman collaboration.

• The programme also included Grand Pianola Music by John Adams (no Pianolas involved), and Julio d’Escriván’s ingenious and expressive Ayayay! Concerto for iPhone, Pianola and orchestra.

November 25, 2009 Comments Off on Ballet mécanique in Cambridge

Renaissance Music at Lincoln Castle

I was in Lincoln recently for the glorious Weekend at the Asylum Steampunk Convivial (you can find a selection of my pictures of that event here). Wandering around the centre of Lincoln as the event wound down on the Sunday afternoon, I stumbled across this group of musicians playing live in the heart of the old castle.

This video is very impromptu and hand-held – essentially little more than a stringing together of a few different shots – but you can experience the atmosphere of the performance (albeit with a touch of wind-noise from time to time).

Kudos to the City of Lincoln Waites for their excellent playing and for the fact that they persevered despite it being quite cool and breezy.

Instruments played include a variety of percussion instruments; the sackbut (predecessor to the trombone); various recorders; a rackett (the compact reed instrument played occasionally by one of the performers seated on the step); a shawm or two (predecessor of the oboe); and a sopranino rauschpfeife shown below (played in some pieces by the woman on the right in the video), which has no modern equivalent. It’s a capped reed instrument (like a bagpipe chanter: your lips do not touch the reed as in modern woodwinds) with a conical bore; it’s a relative of the crumhorn but a good deal louder and more difficult to play (as it easily overblows).

Apart from the recorders this would probably have been described as a “loud band”, playing the kind of instruments you would expect to hear outdoors at public events.

Postscript

I heard today (6 October) from Al Garrod, the Master of the City of Lincoln Waites – the name of the band playing in this video. Al is the sackbut player. Do please visit their site and if you get the chance to hear them, I recommend them highly.

September 23, 2009 Comments Off on Renaissance Music at Lincoln Castle